On April 10, Jem Bendell wrote a detailed and thoughtful article in response to my critique of Deep Adaptation, “What Will You Say to Your Grandchildren.” I appreciate the care he took to ponder my arguments, note where he concurred, and refute what he felt was wrong. I believe that Jem and I agree on much more than we disagree, and that we share a similar heartbreak at the unfolding catastrophe our world is experiencing.

However, as I read Jem’s refutations, I was concerned that some deeper issues are at stake that need to be brought to the surface, and I’m writing this response accordingly. I hope our public dialogue has so far been of value to those who care passionately about what’s happening to our planet and civilization, and that this article continues to move the conversation forward in a constructive fashion.

Articles referred to in this piece:

What Will You Say to Your Grandchildren? by Jeremy Lent, April 4, 2019

Responding to Green Positivity Critiques of Deep Adaptation by Jem Bendell, April 10, 2019

Is collapse likely—or inevitable?

Jem implies that I may have “misrepresented the concept” of Deep Adaptation by failing to read his original article. On the contrary, when I became aware of his article, I was driven to read it thoroughly. I’ve spent years researching the topic of civilizational collapse, which I cover at length in the final chapter of The Patterning Instinct. Having read extensively on the topic, I felt I understood the issues reasonably well. (Bibliography below for anyone interested in researching it further.)

Collapse, in my view and in the view of many thinkers I respect, is a real near-term possibility, perhaps even likely, but not certain. For example, Paul and Anne Ehrlich, whose work I admire tremendously, wrote an article in 2013 entitled “Can a collapse of global civilization be avoided?” They concluded: “The answer is yes, because modern society has shown some capacity to deal with long-term threats. . . but the odds of avoiding collapse seem small.” Regardless of the odds, they aver, “our own ethical values compel us to think the benefits to those future generations are worth struggling for, to increase at least slightly the chances of avoiding a dissolution of today’s global civilization as we know it.”

Now, Jem was claiming to have discovered that collapse was, in fact, inevitable. I was keen to see what new information or methodology he’d uncovered that changed the picture so dramatically. But after carefully reading his paper, I didn’t find anything new of significance. What I noticed was that Jem kept slipping between the terms “inevitable” and “likely” in his analysis. He introduces his paper with the declaration that there will be an “inevitable near-term social collapse due to climate change . . . with serious ramifications for the lives of readers.” Then, about halfway through, he inserts the terms “probable” and “likely.” He opines that “the evidence before us suggests that we are set for disruptive and uncontrollable levels of climate change, bringing starvation, destruction, migration, disease and war.” “The evidence is mounting,” he goes on, “that the impacts will be catastrophic to our livelihoods and the societies that we live within.” On that basis, he declares: “Currently, I have chosen to interpret the information as indicating inevitable collapse, probable catastrophe and possible extinction.”

Quite honestly, I was disappointed by the lack of academic rigor in Jem’s arguments. I greatly appreciate that his article has galvanized many people who were previously numb to the climate crisis, but if I were a reviewer on his academic committee, I would also have rejected it for publication—not because of its “alarmist” character, but simply because it doesn’t adhere to academic standards by constantly jumping from factual evidence to personal opinion without clarifying the distinction.

I respect Jem’s right to interpret the data as he chooses. But what is there, beyond his gut feeling, that should persuade the rest of us that collapse is inevitable? There is, of course, no doubt that the climate news is terrifying and getting worse. However, much of the data is open to interpretation, even among leading experts in the field. As an example, Michael Mann, whose reputation as a climate scientist is virtually unsurpassed, and who has been the target of virulent attacks from climate-deniers, has criticized the predictions of David Wallace-Wells’s New York Magazine article that became the basis for Uninhabitable Earth, as follows:

The article paints an overly bleak picture by overstating some of the science. It exaggerates for example, the near-term threat of climate “feedbacks” involving the release of frozen methane (the science on this is much more nuanced and doesn’t support the notion of a game-changing, planet-melting methane bomb. It is unclear that much of this frozen methane can be readily mobilized by projected warming).

Also, I was struck by erroneous statements like this one referencing “satellite data showing the globe warming, since 1998, more than twice as fast as scientists had thought.” That’s just not true.

The evidence that climate change is a serious problem that we must contend with now, is overwhelming on its own. There is no need to overstate the evidence, particularly when it feeds a paralyzing narrative of doom and hopelessness.

He’s joined by a number of other highly reputable climate scientists making similar criticisms.

I’m not taking sides on this debate. I don’t feel qualified to do so (and I wonder how qualified Jem is?). I’m merely pointing out that the data is highly complex, and subject to good faith differences in interpretation, even among the experts.

Jem wrote in his response to my article that “to conclude collapse is inevitable is closer to my felt reality than to say it is likely.” If he chooses to go with his gut instinct and conclude collapse is inevitable, he has every right to do so, but I believe it’s irresponsible to package this as a scientifically valid conclusion, and thereby criticize those who interpret the data otherwise as being in denial.

The flap of a butterfly’s wings

This is more than just a pedantic point on whether the probability of collapse is actually 99% or 100%. An approach to our current situation based on a belief in inevitable collapse is fundamentally and qualitatively different from one that recognizes the inherent unpredictability of the future. And I would argue that a belief in the inevitability of collapse at this time is categorically wrong.

The reason for this is the nature of nonlinear complex systems. Jem repeatedly describes our climate as nonlinear in his paper, but seems to understand this as simply meaning a rising curve leading to accelerating climate change. Our Earth system, however, is an emergent process derived from innumerable interlinking subsystems, each of which is driven by different dynamics. As such, it is inherently chaotic, and not subject to deterministic forecasting. This is a major reason to be fearful of the reinforcing feedback loops that Jem points out in his paper, but it’s also a reason why even the most careful computer modeling is unable to forecast future changes with anything close to certainty.

When we try to prognosticate collapse, we’re not just relying on a long-term climate forecast, but also on the impact this will have on another nonlinear complex system—human society. In fact, as I describe in the Preface to The Patterning Instinct, human society itself is really two tightly interconnected, coexisting complex systems: a tangible system and a cognitive system. The tangible system refers to everything that can be seen and touched: a society’s technology, its physical infrastructure, and its agriculture, to name just some components. The cognitive system refers to what can’t be touched but exists in the culture: a society’s myths, core metaphors, hierarchy of values, and worldview. These coupled systems interact dynamically, creating their own feedback loops which can profoundly affect each other and, consequently, the direction of society.

The implications of this are crucial to the current debate. Sometimes, in history, the cognitive system has acted to inhibit change in the tangible system, leading to a long period of stability. At other times, the cognitive and tangible systems each catalyze change in the other, leading to a powerful positive feedback loop causing dramatic societal transformation. We are seeing this in today’s world. There is little doubt that we are currently in the midst of one of the great critical transitions of the human journey, and yet it is not at all clear where we will end up once our current system resolves into a newly stable state. Yes, it could be civilizational collapse. I’ve argued elsewhere that rising inequality could lead to a bifurcation of humanity that I call TechnoSplit, the moral implications of which are perhaps even more disturbing than full-blown collapse. And there’s a possibility that the cognitive system transforms into a newly dominant paradigm—an ecological worldview that recognizes the intrinsic interconnectedness of all forms of life on earth, and sees humanity as embedded integrally within the natural world.

There’s another crucial point arising from this understanding of complex systems: each of us plays a part in directing where that system is going. We’re not external observers but intrinsic to the system itself. That means that the choices each of us makes have a direct—and potentially nonlinear—impact on the future. It’s a relay race against time in which every one of us is part of the team. It’s because of this dynamic that I feel it’s so important to counter Jem’s Deep Adaptation narrative. Each one of us can make a difference. We can’t know in advance how our actions will ripple out into the world. As the founder of chaos theory, Edward Lorenz, famously asked: “Does the flap of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil set off a tornado in Texas?” His point was not that it will set off a tornado, but that if it did, it could never be predicted. Will your choice about how you’re going to respond to our current daunting crisis be that butterfly’s wing? None of us can ever know the answer to that.

Deep Transformation means transforming the basis of our civilization

As I pointed out in my article, I agree with Jem wholeheartedly that incremental fixes are utterly insufficient. We need a fundamental transformation of society encompassing virtually every aspect of the human experience: our values, our goals and our collective behavior. The meaning we derive from our existence must arise from our connectedness if we are to succeed in sustaining civilization: connectedness within ourselves, to other humans, and to the entire natural world.

Climate change, disastrous as it is, is just one symptom of a larger ecological breakdown. Just like a patient with a life-threatening disease exhibiting a dangerously high temperature, the symptoms need to be addressed as an emergency, but for long-term health, the underlying disease must be treated. As I describe in The Patterning Instinct—and I understand Jem agrees with me here—the underlying disease in this case is one of separation: separation of mind from body, separation from each other, and separation from nature. It’s our view of humans as essentially disconnected, begun in agrarian civilizations, exacerbated with the Scientific Revolution, and institutionalized by global capitalism, that has set us on this current path either to collapse or TechnoSplit.

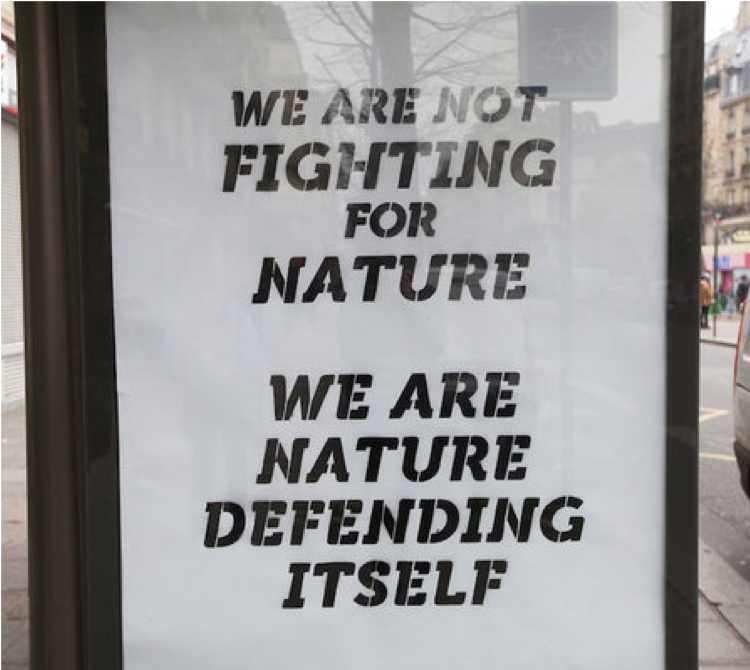

I therefore share with Jem the view that those who argue incremental change can save us are deluding themselves. In my view, even if an assortment of economic and technical fixes were, by a miracle, to reduce atmospheric carbon rapidly enough to avert the worst feedback effects, this wouldn’t be sufficient to avert disaster. We need to transform our core human identity, to rediscover the truth behind the slogan plastered on the streets in Paris during COP21: “We are not fighting for nature. We are nature defending itself.”

In fact, I join Jem in recognizing that, since our current civilization has caused this calamity, perhaps we should “give up on it.” However, the way in which we leave this civilization behind, and what it’s replaced by, are all-important. An uncontrolled collapse of this civilization would be catastrophic, leading to mega-deaths, along with the greatest suffering ever experienced in human history. I’m sure Jem agrees with me that we must consider anything in our power to try to avoid this cataclysm.

I believe the only real path toward future flourishing is one that transforms the basis of our civilization, from the current one that is extractive and wealth-based, to one that is life-affirming, based on the core principles that sustain living systems coexisting stably in natural ecologies. Some of us call this an Ecological Civilization. Jem disparages this vision as a “fairytale.” In fact, as I detail elsewhere, innumerable pioneering organizations around the world are already planting the seeds for this cultural metamorphosis. From buen vivir in South America, to Mondragon in Spain, to the Earth Charter initiative, brave visionaries are living into the future we all want to see.

We don’t know how successful we will be, but let’s give it our best shot. When Thomas Paine wrote The Rights of Man in 1792, he was tried and convicted in absentia by the British for seditious libel. His ideas were also dismissed as a fairy tale. In fact, he and other visionaries of his generation spent their last years believing they had failed. They had no way of knowing that, a hundred and fifty years later, the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights would recognize fundamental human rights as deserving worldwide legal protection. Granted, we don’t have a hundred and fifty years to transform our civilization. But in an age where cultural memes spread virally around the world in hours, I don’t think we should give up on the possibility.

Our profound moral obligation

Jem’s program of Deep Adaptation is based partially on the notion that despair, rather than hope, is the most effective vehicle for transformation. “It turns out,” he writes, ‘that despair can be transformative” by enabling a person to “drop past stories of what is sensible or not.” Ultimately, as he tells it, a call for hope might make people “feel better for a while,” but they will reach a point where “they can’t avoid despair anymore,” at which point they should “let it arise and ultimately transform their identity.”

From personal experience, I feel what Jem is describing. There have been times when I have found myself sobbing uncontrollably with seemingly limitless grief at the enormity of our civilization’s vast ongoing crime of ecocide. I recognize only too well how a false hope that, “somehow things will be better if we can only improve our technology, recycle more, or go vegan,” can cause continual suffering, emotional paralysis, and political incrementalism. We need to open our hearts to the agony of the truth that we’re facing—to the loss of our living earth, to the devastation already being wrought on millions of climate refugees around the world. When we do that, we need spiritual sustenance. We need compassionate community support. Each of us needs to find our way through the quagmire of despair.

Jem—I’m with you on that. I appreciate how your narrative has touched a nerve in so many people, and how you’re devoting your time to building support structures for the grieving that is part of our new reality. But I don’t think it ends there. I believe that hope has a crucial role in healing, and in driving our engagement in effecting the deep transformation we need. When you write that “All hope is a story of the future rather than attention to the present,” I believe you’re showing a profound misunderstanding of what hope really is.

Hope is not a story of the future, it’s a state of mind. In Vaclav Havel’s famous words, it’s not the belief that things will go well; it “is a deep orientation of the human soul that can be held at the darkest times.” And hope can propel us from that deep place to active engagement. As Emily Johnston—one of the courageous valve-turners who faced prison for shutting down tar sands pipelines—has written: “Our job is not to feel hope—that’s optional. Our job is to be hope, and to make space for the chance of a different future.”

For you, Jem, and those that follow your program of Deep Adaptation, I wish only the best, and I empathize with your embrace of despair. If that is the path that feels most meaningful to you, and leads you to your most effective work, go for it. However, I plead with you not to disparage those who are driven by hope, and working to transform our current destructive civilization. I urge you not to keep repeating that collapse is inevitable; that your approach is the only one that’s realistic; and that other people working toward a positive vision are merely in denial. Instead, please recognize that you really don’t know the future course of our world; that despair at the inevitability of collapse is a gut feeling you experience, but is not based on scientific fact. As a wise man once told me: “Believe your feelings; don’t necessarily believe the stories that arise from them.”

Let’s focus on what we know to be true. Let’s engage generatively to transform what we know to be wrong. Species are disappearing. Millions of people are being uprooted. Those of us in a position of privilege and power are part of the system that is causing this global devastation. We have a profound moral obligation to step up and rebel against the structures that are causing this harm. Whether you come from despair or hope, whether you believe collapse is inevitable or that a flourishing future is possible, join together with your sisters and brothers around you, find ways in which you can alleviate their suffering and energize their potential—and recognize that our collective actions are ultimately what will create the future.

NOTE: This article has been edited and updated, based on correspondence between Jem Bendell and Jeremy Lent in February 2020, which established important points of concurrence between our two perspectives that the original article had not identified.

In the interest of transparency, the original article can be read here in pdf format.

Selected bibliography on civilizational collapse

Recommended Books

Joseph A. Tainter, The Collapse of Complex Societies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988).

Thomas Homer-Dixon, The Upside of Down: Catastrophe, Creativity, and the Renewal of Civilization (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2008).

Jared Diamond, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Survive (New York: Penguin Books, 2005).

Donella Meadows, Jorgen Randers, and Dennis Meadows, Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update (White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green, 2004).

Marten Scheffer, Critical Transitions in Nature and Society (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009).

Jorgen Randers, 2052: A Global Forecast for the Next Forty Years (White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green, 2012).

Paul Raskin, et al., Great Transition: The Promise and Lure of the Times Ahead (Boston: Stockholm Environment Institute, 2003).

Recommended Articles

Paul R. Ehrlich, and Anne H. Ehrlich, “Can a Collapse of Global Civilization Be Avoided?”, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 280, no. 1754 (2013).

Safa Motesharrei, et al., “Modeling Sustainability: Population, Inequality, Consumption, and Bidirectional Coupling of the Earth and Human Systems,” National Science Review 3 (2016): 470–94.

Graeme S. Cumming, and Garry D. Peterson, “Unifying Research on Social–Ecological Resilience and Collapse,” Trends in Ecology & Evolution 32, no. 9 (2017): 695–713.

Marten Scheffer, et al., “Early-Warning Signals for Critical Transitions,” Nature 461 (2009): 53–59.

Marten Scheffer, “Anticipating Societal Collapse; Hints from the Stone Age,” PNAS 113, no. 39 (2016): 10733–35.

Richard C Duncan. “The Life-Expectancy of Industrial Civilization.” Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 1991 International System Dynamics Conference, 1991.

Ugo Bardi. “The Punctuated Collapse of the Roman Empire.” In Cassandra’s Legacy. Florence, 2013.

Karl W. Butzer, “Collapse, Environment, and Society,” PNAS 109, no. 10 (2012): 3632–39.

Jeffrey C. Nekola, et al., “The Malthusian–Darwinian Dynamic and the Trajectory of Civilization,” Trends in Ecology & Evolution 28, no. 3 (2013): 127–30

Joseph Wayne Smith, and Gary Sauer-Thompson, “Civilization’s Wake: Ecology, Economics, and the Roots of Environmental Destruction and Neglect,” Population and Environment 19, no. 6 (1998): 541–75.

Joseph A. Tainter, “Resources and Cultural Complexity: Implications for Sustainability,” Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 30, no. 1–2 (2011): 24–34

Graham M. Turner, “A Comparison of the Limits to Growth with 30 Years of Reality,” Global Environmental Change 18 (2008): 397–411.

Jeremy Lent is author of The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity’s Search for Meaning, which investigates how different cultures have made sense of the universe and how their underlying values have changed the course of history. He is founder of the nonprofit Liology Institute, dedicated to fostering a sustainable worldview. For more information visit jeremylent.com.

Looking at the list of just the popular books at the bottom on your latest post, you are better read on collapse than I am. But my elves have been ruminating on collapse for a long time.

I’ve been a science fiction reader ever since discovering Arthur Clarke in 6th grade 65 years ago. I’ve seen some of the devices and the changes come to pass — or not come to pass.

When changes have come to pass it’s never as simple as portrayed; and when things fail, it’s often due to some entire overlooked aspect — usually economic or social.

I am heartened that installing new renewables is now cheaper than building new coal, even in climates like Germany.

I am heartened that electric vehicles are starting to take off.

I am heartened that while the colossus that is the U.S. as a whole marches like lemmings to the sea, individual jurisdictions within it, are taking more sensible paths.

***

I see three forms of collapse likely. Different groups have varying levels of vulnerability to them.

1. Ecological collapse or abrupt modification. In one sense ecologies rarely collapse. There is always an ecology present. However sometimes the change is very fast, very large, and results in a drastic drop in bio-diversity. Let’s call a change that results in a shift in the primary producers, a drop of over 50% in primary production (photosynthesis carbon fixed) and a drop of over 50% in diversity a collapse. By this measure, a forest fire is a collapse. The clearing of forests for agriculture is a collapse, the conversion of grassland to desert is a collapse.

This is happening in the oceans. Fisheries are failing. Corals are bleaching.

I’m facing one where I live in Alberta. The “Business as Usual” scenario put us up 6 C by 2080. At present in the southern end of the province we have dry mixed grass prairie. Most agriculture in the dry mixed grass region is irrigated. Further to the north, where the evaporation is slightly less, and the rains slightly more regular, it’s dryland grain farming. Wheat, oats, peas, canola. Some pasture. Some hay. Where I am in Edmonton, we have Aspen Parkland. Still dryland grain farming mostly.

By 2080, the sagebrush country will extend to almost the northern border. Oh, the existing trees won’t just keel over. But there won’t be young ones. It will be too dry for them to start. Forest fires will be more severe, and replanting forests will be less effective, or will required more desert adapted species.

In Alberta, we won’t have masses of people dying from this. I suspect that agriculture and forestry will take a serious hit, with at least half the jobs vanishing. But it will mostly happen in slow motion. We will adapt. Farms will get larger, as summer fallow to save water becomes the order of the day. Spruce forests will give way to douglas fir, larch, and pine.

In third world countries, ecological collapse will kill. If you grow 1.5 times as much as you eat in a good year and half as much as you eat in a bad year, you break even, if the good years outnumber the bad. But get a string of bad years, and the four horsemen ride, and you have hundreds of thousands of people scrambling for what little is left.

2. Economic collapse. This can be global or local depending which domino falls first. Given the U.S. actions under the Trump Administration, I would not be surprised to see the U.S. fail as a nation. In 2008, Obama stepped in and propped up the banking system. There is nothing to stop this from happening again, and Trump’s reactions to crisis depend on what he’s heard on Fox News that morning.

The economy, and money in general, is a shared delusion: The idea is that you accepted fancy strips of paper for your goods in the past, and so you will do so tomorrow. But it’s a house of cards, and we have many historical examples of how fast it can collapse. By their nature, forecasting them is difficult. Good examples of tipping points.

An economic collapse will hurt the first world countries the most. Trade slows. Economies stop investing in their own future. The switch away from coal slows. Social services are cut. Deathrates climb.

An economic depression probably shouldn’t be considered a collapse. Even the 1928 depression didn’t leave half the people out of work. The Weimar Republic in Germany is probably a better example.

3. Social collapse — the failure of governments, balkanization. We see this happening in Venezuela. Civil war is one form of social collapse. A good example is the disintegration of Yugoslavia. I wonder if we are seeing the early stages of this in the U.S. Will we see California as it’s own nation?

Of course it won’t be clear cut like this: A crop failure from a plague of locusts may be the ecological trigger of a civil war. A banking system collapse may halt the adaptation of a region that otherwise was making decent progress.

Ok, Sherwood, what’s your point:

Point 1: It won’t be “A collapse” It’s going to be a series of collapses. Most of them are going to be regional, not international.

Point 2: People are going to be wrapped up in their local problems, and won’t pay attention to the world problems.

LikeLiked by 3 people

A thoughtful, concise and very articulated post, SG. I am not being condescending, only trying to come to grips with my shock.

You see, I too am from Edmonton. There are a few, too darn few, good writers and bloggers in Alberta who have the experience, intellectual capacity and interest to embark on an analysis of our current circumstances. None, I’m afraid, have the insight and courage to lay out the premises and derive the logical conclusions as you.

Given what I see and hear locally, I thought it was impossible that such thinking could happen here. It has been a great source of despair, loneliness, indeed, even fear for me over the last decades to have such knowledge and understanding while being surrounded by people so hell-bent on continued destruction using fraudulent claims of science and economics and discredited business and political practices.

Oh!, it’s a happy day to discouver your voice. I hope to read much more from you SGBOTSFORD.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Chortle. (Us old farts can chortle, yes?)

More of my writing, if you care is on Quora, Medium, Reddit, and Stack Exchange.

I’m giving up on Quora, as the same questions keep coming up, without any effort to look for answers. Nor is it possible to ask a nuanced question on Quora anymore, since they no longer allow an explanatory background to the question.

Medium now charges to be a member. I will not pay to write.

Reddit has enough specialized sub-reddits to have some interest for me. Like Quora it suffers from “That one again” but not because you can’t have a body (and substance) to your question, but rather that Reddit has an awful search engine.

Stack Exchange is also partitioned, but has a meaningful rating system. Tends to take itself too seriously in some exchanges.

My treefarm website is at http://sherwoods-forests.com

LikeLike

well said, echoing John Michael Greer and others about a stepwise collapse. I take issue with Lent’s criticism of Bendell as being ‘academically unrigorous’. Lent’s whole paper is a series of belief statements, with which he helpfully predicates each one. Moreover he doesn’t define his terms; specifically collapse, as you have here. Finally, he ignores (for the time being; a later essay lays out the 5 ‘conspiracies’ to be worried about) the tremendous momentum that has been in play for a decade at least, for a Great Reset, orchestrated by the ‘greatest’ among us. See Catherine Fitts’ interview for the doc, Planet Lockdown here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C1-0XKYAZII&feature=emb_logo

ps. Lent does not address the reality of human capacity for denial, as your fellow Albertan does on his blog Un-denial.

LikeLike

Strategic Plan. Love everyone. Hate no-one. Move to the edge. Thank you Jeremy – I can begin to breathe.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The problem is that this is way above most people’s heads, difficult to understand, a challenge to come to terms with and impossible to imagine what life might be like afterwards – in short, overwhelming. Mostly they can’t conceive of any life other than the one they are presently living, of business as usual. We shouldn’t encourage people to think that our decaying global political systems and massive environmental crises are going to allow our daily lives to continue as they are. People grab hold of any tiny piece of hope as a lifeline, a connection to what they know and it can prevent them from moving in the direction they ought to or from bracing themselves for massive change. You say that you and Jem agree more than disagree, so maybe you and your colleagues working in this field, using what you agree on, can help us see how we can begin adapting and transforming the way we live in readiness.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think it was Larry Niven’s novel “Footfall” a classic alien invasion story, the military brought in a bunch of science fiction writers of the ‘hard sf’ category. Sci-fi with rivets, with good science, working economies.

SF authors and readers have a different view of change:

Most people see the world as unchanging. Outside of a few tech changes that hit them directly like computers and cell phones, they see the world tomorrow as being more or less the world of today.

Most futurists and scientists see the world of tomorrow as being a linear extrapolation of the world of today. This is why the IPCC estimates have tended to be very conservative, and actual change is running about their worst level forecasts.

A few SF writers see that the change itself has re-organization changes.

Examples:

When the auto replaced the horse.

* Rich man’s toy. Too expensive for everyday use.

* A few city planners saw that if it replaced the horse we wouldn’t have to clean all that horse crap off the street.

* Some very insightful people saw the rise of suburbs, and a few the traffic problems.

* No one saw the change it would make to courtship and dating.

LikeLike

I did a site search here and at Bendell’s blog. I didn’t find any mention of the Bronze Age Collapse or the Little Ice Age behind the General Crisis.

Those are the two main historical examples of widespread environmental stress and turmoil. The Little Ice Age, although lasting for centuries, was minor in comparison to the mass catastrophe that brought ended most of the great civilizations in the late Bronze Age.

It seems like considering those examples could be helpful in understanding the situation we now face with its possible outcomes. There are other examples that could be brought up, but those two were no doubt formative to what followed.

I’d be curious what others here might think about this.

Climate Change and the Course of Global History: A Rough Journey

by John L. Brooke

Megadrought and Collapse: From Early Agriculture to Angkor

edited by Harvey Weiss

Third Millennium BC Climate Change and Old World Collapse

edited by H. Nüzhet Dalfes, George Kukla, and Harvey Weiss

Civilizing Climate: Social Responses to Climate Change in the Ancient Near East

by Arlene Miller Rosen

1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed

by Eric H. Cline

The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850

by Brian Fagan

Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century

by Geoffrey Parker

A Cold Welcome: The Little Ice Age and Europe’s Encounter with North America

by Sam White

The Frigid Golden Age: Climate Change, the Little Ice Age, and the Dutch Republic, 1560–1720

by Dagomar Degroot

The General Crisis of the Seventeenth Century

edited by Geoffrey Parker, and Lesley M. Smith

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for this back-and-forth with Bendell; you two explore important issues, illuminated all the better by the different perspective you each bring. As you note in your opening to this response, you and he agree in most areas, and seem to have similar values and goals. I’m sensing that your main disagreements may be more semantic than substantive, especially around “civilization” and “hope,” which people often define in very different ways.

I first learned of your work through the Resistance Radio interview of you by Derrick Jensen, who defines civilization as characterized by the growth of cities which degrade their land with agriculture, making both cities and civilization inherently unsustainable. Jensen advocates proactively dismantling civilization and transitioning to sustainable cultures based on the needs and the gifts of the land in each particular place. Bendell also seems to see civilization as inherently incompatible with sustainability, so has found inner peace with giving up on it. Your term “ecological civilization” is an oxymoron by Jensen’s definition, yet clearly you have a solid understanding of anthropology, history, collapse, ecology and ecopsychology; and you seem to have a biophilic orientation, so I suspect you envision a similar transformation but are using a different definition of civilization than is Jensen. (I look forward to reading The Patterning Instinct!)

Similarly, Jensen defines hope as “a longing for a future condition over which one has no agency,” by which definition hope is inherently disempowering and demotivating. I think Bendell’s definition is similar, but you’re clearly using a different definition when you uphold hope as important for driving engagement.

You and Bendell have somewhat different evaluations of the probabilities of different collapse scenarios, and perhaps disagree over whether effective changes can still be made at large (national & international) scales, but you both desire radical transformation of society into a way of life which sustainably nurtures humans and their landbases. You both want to motivate people to participate proactively in the transformation, rather than being reactive victims of collapse. Again, thank you for this dialogue, and more generally, thank you for all your work to that end.

This piece may be of interest to you and your readers: From Reform to Devolution: Jem Bendell’s Deep Adaptation. It aligns more with Jensen’s and Bendell’s definitions and interpretations than with your own (as I understand them without yet having read your book). It holds no “hope” for large-scale transformation of industrialism to a sustainable way of living, but advocates working at household and community scales to prepare and proactively transition…while stopping industrial systems from degrading any more of the ecological communities on which humans depend. While it accepts collapse as highly likely, it suggests that those of us living now have more opportunity for meaningful work than any previous generations, with the chance to leave a broader and longer lasting legacy than was ever possible before. Accepting collapse needn’t mean giving up on action; it does mean rethinking what action makes sense under these circumstances. To finish with Jensen’s perspective again: the dividing line is not between those who work in the mainstream vs grassroots, not between those who work to prepare their communities for collapse vs work to change broad culture beliefs; the dividing line is between those who do something and those who do nothing. I think we can all agree on that.

LikeLike

Norristh: As I observe what’s happening to the natural world–I am active in nature conservation–, it seems clear to me that humankind in our present technological civilization are on a collision course with the biosphere. This is in itself the big ethical issue of our time. Do we have the right to drive a Sixth Mass Extinction? So I wonder at people grieving at the collapse of a civilization whose core values are to exploit as intenseivley and extensively as possible the resources of the Earth to produce consumer goods. We urgently need a new civlization–I understand the world civilization to mean that there is some law and order in society.

LikeLike

“Politics is the art of the Possible”

A set of non-technological sustainable cultures is impossible for two reasons:

A: It requires 95% of the human race to die. The population of North America was about 25 million when Columbus arrived. That was around the maximum supportable number of people using the then present technology.

Oh, yes. They had tech. Fire. Agriculture. Pottery. Flint knapping.

Eastern North American natives burned off the understory of the forests to make better habitat for deer. You actually could run under the trees as in “Last of the Mohicans” Now going through a wild section of the eastern hardwood forest is a fight.

B: Hunter/gatherer and subsistence farmers are not the gentle touch on the earth. The Spanish brought horses to the western hemisphere, and they exploded across the plains. This was a new technology. The buffalo hunters killed off the great herds, but the natives would have done it themselves in another 50 years. A controversial theory: The arrival of tribes over the Bering Straight land bridge was the doom of the megafauna in north America.

There’s a reason that so much of Africa is desert. Some is changing climate. Most is over grazing. Ditto Greece. Ditto the Middle East.

The answer is not less tech, but more tech. More tech and better understanding of human psychology, and a better understanding of natural systems.

I grew up in a town of about 10,000. I didn’t act out. I knew that my mom knew enough people in town, that word of anything really interesting I did would get home before I did.

Most people know about a hundred people. Immediate family. Some of their neighbours. Co-workers. Oldtimer’s hockey league. Some of their kid’s school teachers. People at church. Kid’s friend’s parents. You’ve heard of the game “7 degrees of Kevin Bacon” Or similarly that some small number of links connect any two people. The number cited varies from 5 to 7.

I propose the following:

* A hamlet is the maximum number of people where everyone knows pretty much everyone. Link count 0. 50-140 people. The golden rule and a few reminders work at this level. I worked in a private boarding school with 90-120 students, and 15-20 staff. Lot of the social mechanisms were breaking down at the upper end of that. Less flying the the seat of your pants, and more rules. This is your local band.

* A village is the maximum number of people where *some* of them know everyone in the village. The link count is 1. I know Elder Speerling. She knows Susan. Somewhere between 100-400.

* A town is requires a link count of 2. Lots of, “Let me inquire, I may know someone who can help” Somewhere in the high hundreds to low thousands.

* A city requires a link count of 3. Lots more rules, lots more procedures to follow, but the links allow things to work anyway. 40,000 to 200,000

As the link count grows, our ‘community’ becomes more dispersed. If work is a 45 minute commute to the other side of town, then we see those people only at work, and not sharing a bleacher watch little league. Unless we seek people out, most of the people we see are total strangers. We live in multiple partial villages.

Our cities are failing. We need to rebuild them with better first level links:

Rebuild our cities as clusters of towns, which are in turn clusters of villages. Most of this can be done just by rezoning. Our biggest mistakes was to separate business from residential. Some businesses should be separated. The ones that stink; the ones that are making loud noises 24 hours a day. But all the B2B firms that run 8 to 5, all the corner grocery stores; all the shops, the offices, the professionals like dentists and lawyers. There is no reason why they can’t be mixed in residential areas.

There is no reason why a tower downtown can’t be designed as an arcology: A single building with shops, and offices and residences, and schools, and floors that are playgrounds, and parks on the roof.

We need to make our cities walkable again.

(If you want an interesting look at this culture, read “Oath of Fealty” by Larry Niven.)

Certainly we have major issues with big ag. I think we need to take a good look at the Amish. The descriptions I’ve read of their internal culture sound repressive, but there is a lot of merit in their method’s of agriculture. I don’t know if it would work well on the prairie. Most of the Amish settlements are in what used to be the eastern hardwood forests — more rain, generally higher net productivity. Fewer calamitous weather events.

One of the problems with ag is there is no room for bugs. “Get big or get out. Farm from edge to edge. That means no weeds to feed the bees. That means no habitat for the wasps that prey on the aphids.

We don’t understand ecology very well. Indeed, we are far from a true science of ecology, in the sense that it is predictive. At best we understand some of the gross motions. But one general things has come out, at least in my readings:

Simple ecologies are less stable. I spent a week trying to model a very simple system — grass + sheep + wolves. Either the sheep eat all the grass and starve. Or the wolves eat all the sheep and starve. Make it more complex: Add shrubs and rabbits. Sheep don’t like shrubs. Makes them easy to catch. Rabbits feed on shrubs, but also on grass, and hide in the shrubs from the wolves. Wolves prefer sheep, but will eat rabbit (more work…) when lamb isn’t around. This was much more stable.

Keys to stable ecologies: Diversity. Any grazer that depends on a single species (Monarch butterfly and milkweed) and predator that depends on a single prey species (many wasps) is going to be subject to violent cycles in population, sometimes creating local extinction events.

In one sense our urban villages are suffering from a lack of diversity.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As a USAF scientist for the last 20 years, I’ve reviewed the literature at the top scientific level (Rockstrom, et al., Anderson, et al., Wadhams, et al., IPCC SR15, etc.) – including less “hard-core” science such as Tainter, Diamond, Hedges, Nikiforuk, Ghosh, Greer, etc.

I find the arguments for collapse of civilization compelling and well-founded physically, and the arguments for Merchants Of Doubt style denialism entirely consistent with these findings.

Thus I find Bendell’s analysis essentially correct. Top level scientists (Wadhams, Rockstrom, and Anderson, for instance) are clearly indicating we will fail and civilization will collapse. At this point, science fails to be able to predict and that’s where Bendell and Read come in. It’s clear that some places will have Somalia-style dying zones, and other places will be less affected. We have already essentially lost the war against bacteria, and much more will be lost as global civilization collapses. Some (particularly in the US) seem to prefer the “armed lifeboat” strategy, but history has shown ultimately this cannot work, especially since Planetary Boundaries (Rockstrom, et al.) of N/P Cycle disruption and biodiversity loss are FAR worse than simple runaway climate change, which has become evident within the last year or so.

Thus, it is reasonable that a catastrophic collapse is likely. Given recent predictions about ultimate temperature we’re heading toward, an end-permian-style mass extinction is possible. The question is: could bands of humans survive an end-permian-style mass extinction? Possibly.

LikeLike

The lifeboat scenario as I understand it, is trump wallism writ large. Refugees will be shot at the border. Borders will be mined. Small naval vessels with 2″ guns will sink refugee boats.

There will be leakage — survivors from sinkings, people who clamber over difficult rocky terrain, or wade soggy marshes. Drop in the bucket. Most equatorial country inhabitants won’t have the resources to move out of the famine zones. Few people will walk from Somalia to Germany. Somewhere around 2 billion people in tropical regions will die.

I’m unconvinced of a permian level extinction event yet. I do think we will see wide spread ecological collapse.

That latter requires some definition: There will almost always be an ecology, but will it be the same one? When a forest fire burns the woods down to dirt, a year later you have a thriving ecosystem of seedlings, fireweed, poplar… This is the normal for a fire succession ecology — but the ecology is markedly changed.

* Population drop in dominant species.

* Lower biodiversity

* Lower gross productivity (CO2 converted to carbohydrate)

I’m uncertain about the levels of each of these that would constitute a collapse. I am going to be arbitrary and if the sum of all these 3 factors are 150%, then you have a collapse, although you may want to call them “transitions”

Alberta (where I live) is facing a conversion of Aspen Parkland — the dominant ecosystem in central Alberta — to convert over to mixed grass prairie over the next 40-50 years. Along with it, humans are going to have to adapt their agriculture to a summer fallow, one crop every two years system much like in Grant Country, Washington. (Irrigation by mining the sub surface water can be used to postpone this, but much central Alberta is rolling hills, difficult to irrigate.)

My WAG is that we are going to see a 30% drop overall in world agricultural production in the next 30 years. Causes:

* Decreasing power of the jet stream. Storm systems move more slowly, so that even where the rainfall averages the same per year, the variance or standard deviation increases markedly. We are seeing this in the U.S. now (2019) with the severe flooding that occurred this spring and summer. We saw it when hurricane Harvey sat on Houston for a week.

* Air masses that normally are swept eastward by the jet stream instead have time to ooze further north and further south. We see it in the heatwave that is perched on Europe, and the polar vortex that brought snow to Mississippi, and 50 F above normal temps to Fairbanks, Alaska. We see it today in the near record melt event happening on Greenland right now.

* Net warmer temps mean more water is evaporated. The atmosphere can hold about 7% more water for each degree warmer. The whole hydrologic cycle speeds up. More evaporation, but more rain. Wet air is a good way to move thermal energy. Net results is that the equator warms only a little, but the poles warm a lot. While it will rain more (good, to help compensate for more evaporation) it won’t come down in the same places it went up.

* Rain timing is changing. Monsoons late, early, or not there at all. Heavy rain in early spring delays planting. Heavy rain in mid/late summer delays harvest or destroys crops

LikeLike