Facing oncoming climate disaster, some argue for “Deep Adaptation”—that we must prepare for inevitable collapse. However, this orientation is dangerously flawed. It threatens to become a self-fulfilling prophecy by diluting the efforts toward positive change. What we really need right now is Deep Transformation. There is still time to act: we must acknowledge this moral imperative.

Every now and then, history has a way of forcing ordinary people to face up to a moral encounter with destiny that they never expected. Back in the 1930s, as Adolf Hitler rose to power, those who turned away when they saw Jews getting beaten in the streets never expected that decades later, their grandchildren would turn toward them with repugnance and say “Why did you do nothing when there was still a chance to stop the horror?”

Now, nearly a century on, here we are again. The fate of future generations is at stake, and each of us needs to be prepared, one day, to face posterity—in whatever form that might take—and answer the question: “What did you do when you knew our future was on the line?”

Unless you’ve been hiding under a rock the past few months, or get your daily updates exclusively from Fox News, you’ll know that our world is facing a dire climate emergency that’s rapidly reeling out of control. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has issued a warning to humanity that we have just twelve years to turn things around before we pass the point of no return. Governments continue to waffle and ignore the blaring sirens. The pledges they’ve made under the 2015 Paris agreement will lead to 3 degrees of warming, which would threaten the foundations of our civilization. And they’re not even on track to meet those commitments. Even the IPCC’s dire warning of calamity is, by many accounts, too conservative, failing to take into account tipping points in the earth system with reinforcing feedback effects that could drive temperatures far beyond the IPCC’s worst case scenarios.

People are beginning to feel panicky in the face of oncoming disaster. Books such as David Wallace-Wells’s Uninhabitable Earth paint a picture so frightening that it’s already feeling to some like game over. A strange new phenomenon is emerging: while mainstream media ignores impending catastrophe, increasing numbers of people are resonating with those who say it’s now “too late” to save civilization. The concept of “Deep Adaptation” is beginning to gain currency, with its proponent Jem Bendell arguing that “we face inevitable near-term societal collapse,” and therefore need to prepare for “civil unrest, lawlessness and a breakdown in normal life.”

There’s much that is true in the Deep Adaptation diagnosis of our situation, but its orientation is dangerously flawed. By turning people’s attention toward preparing for doom, rather than focusing on structural political and economic change, Deep Adaptation threatens to become a self-fulfilling prophecy, increasing the risk of collapse by diluting efforts toward societal transformation.

Our headlong fling toward disaster

I have no disagreement with the dire assessment of our circumstances. In fact, things look even worse if you expand the scope beyond the climate emergency. Climate breakdown itself is merely a symptom of a far larger crisis: the ecological catastrophe unfolding in every domain of the living earth. Tropical forests are being decimated, making way for vast monocrops of wheat, soy, and palm oil plantations. The oceans are being turned into a garbage dump, with projections that by 2050 they will contain more plastic than fish. Animal populations are being wiped out. The insects that form the foundation of our global ecosystem are disappearing: bees, butterflies, and countless other species in free fall. Our living planet is being ravaged mercilessly by humanity’s insatiable consumption, and there’s not much left.

Deep Adaptation proponents are equally on target arguing that incremental fixes are utterly insufficient. Even if a global price on carbon was established, and if our governments invested in renewables rather than subsidizing the fossil fuel industry, we would still come up woefully short. The harsh reality is that, rather than heading toward net zero, global emissions just hit record numbers last year; Exxon, the largest shareholder-owned oil company, proudly announced recently that it’s doubling down on fossil fuel extraction; and wherever you look, whether it’s air travel, globalized shipping, or beef consumption, the juggernaut driving us to climate catastrophe only continues to accelerate. To cap it off, with ecological destruction and global emissions already unsustainable, the world economy is expected to triple by 2060.

The primary reason for this headlong fling toward disaster is that our economic system is based on perpetual growth—on the need to consume the earth at an ever-increasing rate. Our world is dominated by transnational corporations, which now account for sixty-nine of the world’s largest hundred economies. The value of these corporations is based on investors’ expectations for their continued growth, which they are driven to achieve at any cost, including the future welfare of humanity and the living earth. It’s a gigantic Ponzi scheme that barely gets a mention because the corporations also own the mainstream media, along with most governments. The real discussions we need about humanity’s future don’t make it to the table. Even a policy goal as ambitious as the Green New Deal—rejected by most mainstream pundits as utterly unrealistic—would still be insufficient to turn things around, because it doesn’t acknowledge the need to transition our economy away from reliance on endless growth.

Deep Adaptation . . . or Deep Transformation?

Faced with these realities, I understand why Deep Adaptation followers throw their hands up in despair and prepare for collapse. But I believe it’s wrong and irresponsible to declare definitively that it’s too late—that collapse is “inevitable.” It’s too late, perhaps, for the monarch butterflies, whose numbers are down 97% and headed for extinction. Too late, probably for the coral reefs that are projected not to survive beyond mid-century. Too late, clearly, for the climate refugees already fleeing their homes in desperation, only to find themselves rejected, exploited, and driven back by those whose comfort they threaten. There is plenty to grieve about in this unfolding catastrophe—it’s a valid and essential part of our response to mourn the losses we’re already experiencing. But while grieving, we must take action, not surrender to a false belief in the inevitable.

Defeatism in the face of overwhelming odds is something that I, perhaps, am especially averse to, having grown up in postwar Britain. In the dark days of 1940, defeat seemed inevitable for the British, as the Nazis swept through Europe, threatening an impending invasion. For many, the only prudent course was to negotiate with Hitler and turn Britain into a vassal state, a strategy that nearly prevailed at a fateful War Cabinet meeting in May 1940. When details about this Cabinet meeting became public, in my teens, I remember a chill going through my veins. Born into a Jewish family, I realized that I probably owed my very existence to those who bravely chose to overcome despair and fight on in a seemingly hopeless struggle.

A lesson to learn from this—and countless other historical episodes—is that history rarely progresses for long in a straight line. It takes unanticipated swerves that only make sense when analyzed retroactively. For ten years, Tarana Burke used the phrase “me too” to raise awareness of sexual assault, without knowing that it would one day help topple Harvey Weinstein, and potentiate a movement toward transformation of abusive cultural norms. The curve balls of history are all around us. No-one can accurately predict when the next stock market crash will occur, never mind when civilization itself will come undone.

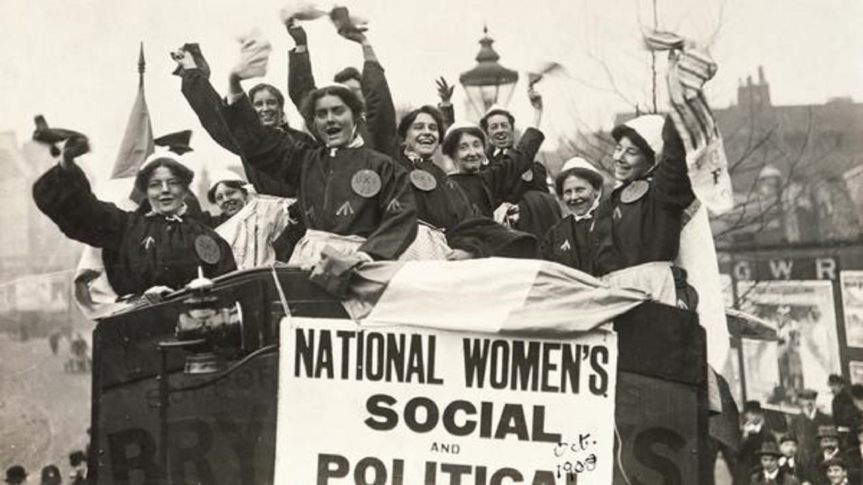

There’s a second, equally important, lesson to learn from the nonlinear transformations that we see throughout history, such as universal women’s suffrage or the legalization of same-sex marriage. They don’t just happen by themselves—they result from the dogged actions of a critical mass of engaged citizens who see something that’s wrong and, regardless of seemingly insurmountable odds, keep pushing forward driven by their sense of moral urgency. As part of a system, we all collectively participate in how that system evolves, whether we know it or not, whether we want to or not.

Paradoxically, the very precariousness of our current system, teetering on the extremes of brutal inequality and ecological devastation, increases the potential for deep structural change. Research in complex systems reveals that, when a system is stable and secure, it’s very resistant to change. But when the linkages within the system begin to unravel, it’s far more likely to undergo the kind of deep restructuring that our world requires.

It’s not Deep Adaptation that we need right now—it’s Deep Transformation. The current dire predicament we’re in screams something loudly and clearly to anyone who’s listening: If we’re to retain any semblance of a healthy planet by the latter part of this century, we have to change the foundations of our civilization. We need to move from one that is wealth-based to one that is life-based—a new type of society built on life-affirming principles, often described as an Ecological Civilization. We need a global system that devolves power back to the people; that reins in the excesses of global corporations and government corruption; that replaces the insanity of infinite economic growth with a just transition toward a stable, equitable, steady-state economy optimizing human and natural flourishing.

Our moral encounter with destiny

Does that seem unlikely to you? Sure, it seems unlikely to me, too, but “likelihood” and “inevitability” stand a long way from each other. As Rebecca Solnit points out in Hope in the Dark, hope is not a prognostication. Taking either an optimistic or pessimistic stance on the future can justify a cop-out. An optimist says, “It will turn out fine so I don’t need to do anything.” A pessimist retorts, “Nothing I do will make a difference so let me not waste my time.” Hope, by contrast, is not a matter of estimating the odds. Hope is an active state of mind, a recognition that change is nonlinear, unpredictable, and arises from intentional engagement.

Bendell responds to this version of hope with a comparison to a terminal cancer patient. It would be cruel, he suggests, to tell them to keep hoping, pushing them to “spend their last days in struggle and denial, rather than discovering what might matter after acceptance.” This is a false equivalency. A terminal cancer condition has a statistical history, derived from the outcomes of many thousands of similar occurrences. Our current situation is unique. There is no history available of thousands of global civilizations bringing their planetary ecosystems to breaking point. This is the only one we know of, and it would be negligent to give up on it based on a set of projections. If a doctor told your mother, “This cancer is unique and we have no experience of its prognosis. There are things we can try but they might not work,” would you advise her to give up and prepare for death? I’m not giving up on Mother Earth that easily.

In truth, collapse is already happening in different parts of the world. It’s not a binary on-off switch. It’s a cruel reality bearing down on the most vulnerable among us. The desperation they’re experiencing right now makes it even more imperative to engage rather than declare game over. The millions left destitute in Africa by Cyclone Idai, the communities still ravaged in Puerto Rico, the two-thousand-year old baobab trees suddenly dying en masse, and the countless people and species yet to be devastated by global ecocide, all need those of us in positions of relative power and privilege to step up to the plate, not throw up our hands in despair. There’s currently much discussion about the devastating difference between 1.5° and 2.0° in global warming. Believe it, there will also be a huge difference between 2.5° and 3.0°. As long as there are people at risk, as long as there are species struggling to survive, it’s not too late to avert further disaster.

This is something many of our youngest generation seem to know intuitively, putting their elders to shame. As fifteen-year-old Greta Thunberg declared in her statement to the UN in Poland last November, “you are never too small to make a difference… Imagine what we can all do together, if we really wanted to.” Thunberg envisioned herself in 2078, with her own grandchildren. “They will ask,” she said, “why you didn’t do anything while there still was time to act.”

That’s the moral encounter with destiny that we each face today. Yes, there is still time to act. Last month, inspired by Thunberg’s example, more than a million school students in over a hundred countries walked out to demand climate action. To his great credit, even Jem Bendell disavows some of his own Deep Adaptation narrative to put his support behind protest. The Extinction Rebellion (XR) launched a mass civil disobedience campaign last year in England, blocking bridges in London and demanding an adequate response to our climate emergency. It has since spread to 27 other countries.

Studies have shown that, once 3.5% of a population becomes sustainably committed to nonviolent mass movements for political change, they are invariably successful. That would translate into 11.5 million Americans on the street, or 26 million Europeans. We’re a long way from that, but is it really impossible? I’m not ready, yet, to bet against humanity’s ability to transform itself or nature’s powers of regeneration. XR is planning a global week of direct action beginning on Monday, April 15, as a first step toward a coordinated worldwide grassroots rebellion against the system that’s destroying hope of future flourishing. It might just be the beginning of another of history’s U-turns. Do you want to look your grandchildren in the eyes? Yes, me too. I’ll see you there.

FURTHER READING

Read Jem Bendell’s response to this article: Responding to Green Positivity Critiques of Deep Adaptation, April 10, 2019

Read Jeremy Lent’s follow-up response to Jem Bendell: Our Actions Create the Future, April 11, 2019.

Jeremy Lent is author of The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity’s Search for Meaning, which investigates how different cultures have made sense of the universe and how their underlying values have changed the course of history. He is founder of the nonprofit Liology Institute, dedicated to fostering a sustainable worldview. For more information visit jeremylent.com.