First published as “Nature Is a Jazz Band, Not a Machine” by Institute of Art and Ideas | News on July 30, 2021.

From genetic engineering to geoengineering, we treat nature as though it’s a machine. This view of nature is deeply embedded in Western thought, but it’s a fundamental misconception with potentially disastrous consequences.

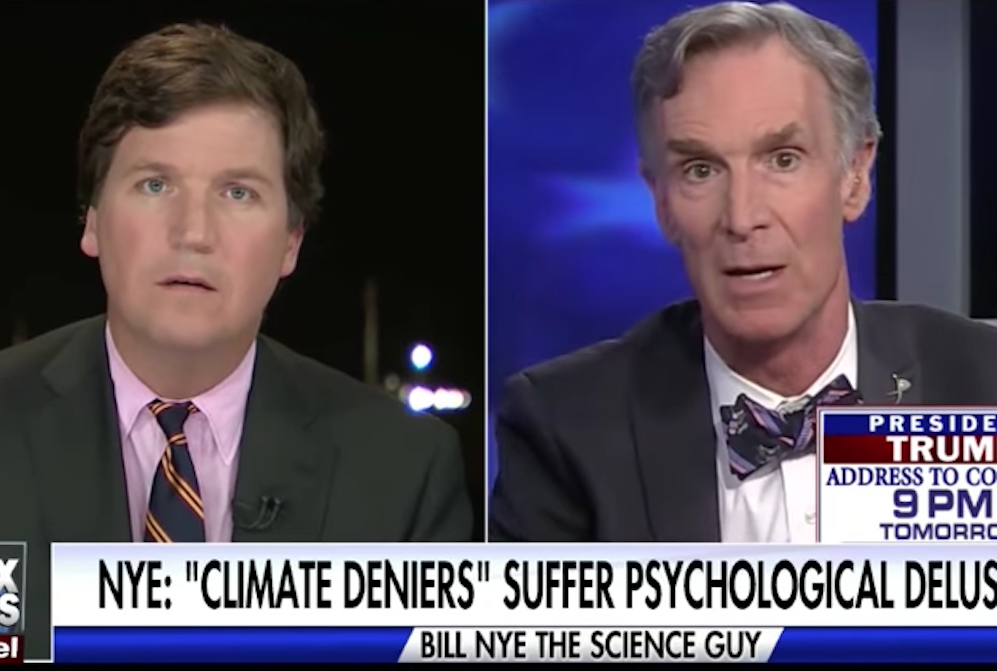

Climate change, avers Rex Tillerson, ex-CEO of ExxonMobil and erstwhile US Secretary of State, “is an engineering problem, and it has engineering solutions.” This brief statement encapsulates how the metaphor of the machine underlies the way our mainstream culture views the natural world. It also hints at the grievous dangers involved in perceiving nature in this way.

This mechanistic worldview has deep roots in Western thought. The great pioneers of the Scientific Revolution, such as Galileo, Kepler, and Newton, believed they were decoding “God’s book,” which was written in the language of mathematics. God was conceived as a great clockmaker, the “artificer” who constructed the intricate machine of nature so flawlessly that, once it was set in motion, there was nothing more to do (bar the occasional miracle) than let it run its course. “What is the heart, but a spring,” wrote Thomas Hobbes, “and the nerves but so many strings?” Descartes flatly declared: “I do not recognize any difference between the machines made by craftsmen and the various bodies that nature alone composes.”

In recent decades, the mechanistic conception of nature has been updated for the computer age, with popularizers of science such as Richard Dawkins arguing that “life is just bytes and bytes and bytes of digital information” and as a result, an animal such as a bat “is a machine, whose internal electronics are so wired up that its wing muscles cause it to home in on insects, as an unconscious guided missile homes in on an aeroplane.” This digital metaphor of nature pervades our culture and is used unreflectively by those in a position to direct our society’s future. According to Larry Page, co-founder of Google, for example, human DNA is just “600 megabytes compressed, so it’s smaller than any modern operating system . . . So your program algorithms probably aren’t that complicated.”

But nature is not in fact a machine nor a computer—and it can’t be engineered or programmed like one. Thinking of it as such is a category error with ramifications that are both deluded and dangerous.

A four-billion-year reversal of entropy

Ultimately, this machine metaphor is based on a simplifying assumption, known as reductionism, which approaches nature as a collection of tiny parts to investigate. This methodology has been resoundingly effective in many fields of inquiry, leading to some of our greatest advances in science and technology. Without it, most of the benefits of our modern world would not exist—no electrical grids, no airplanes, no antibiotics, no internet. However, over the centuries, many scientists and engineers have been so swept up by the success of their enterprise that they have frequently mistaken this assumption for reality—even when advances in scientific research uncover its limitations.

When James Watson and Francis Crick discovered the shape of the DNA molecule in 1953, they used metaphors from the burgeoning information revolution to describe their findings. The genotype was a “program” that determined the exact specifications of an organism, just like a computer program. DNA sequences formed the “master code” of a “blueprint” that contained a detailed set of “instructions” for building an individual. Prominent geneticist Walter Gilbert would begin his public lectures by pulling out a compact disk and proclaiming “This is you!”

Since then, however, further scientific research has revealed fundamental defects in this model. The “central dogma” of molecular biology, as coined by Crick and Watson, was that information could only flow one way: from the gene to the rest of the cell. Biologists now know that proteins act directly on the DNA of the cell, specifying which genes in the DNA should be activated. DNA can’t do anything by itself—it only functions when certain parts of it get switched on or off by the activities of different combinations of proteins, which were themselves formed by the instructions of DNA. This process is a vibrant, dynamic circular flow of interactivity.

This leads to a classic chicken-and-egg problem: if a cell is not determined solely by its genes, what ultimately causes it to “decide” what to do? Biologists who have researched this issue generally agree that the emergence of life on Earth was most likely a self-organized process known as autopoiesis—from the Greek words meaning self-generation—performed originally by non-living molecular structures.

These protocells essentially staged a temporary, local reversal of the Second Law of Thermodynamics which describes how the universe is undergoing an irreversible process of entropy: order inevitably becomes disordered and heat always flows from hot regions to colder regions. We see entropy in our daily lives every time we stir cream into our coffee, or break an egg for an omelet. Once the egg is scrambled, no amount of work will ever get the yolk back together again. It’s a depressing law, especially when applied to the entire universe which, according to most physicists, will eventually dissipate into a bleak expanse of cold, dark nothingness. Those first protocells, however, learned to turn entropy into order by ingesting it in the form of energy and matter, breaking it apart, and reorganizing it into forms beneficial for their continued existence—the process we know as metabolism.

Ever since then, for roughly four billion years, the defining quality of life has been its purposive self-organization. There is no programmer writing a program; no architect drawing up a blueprint. The organism is the weaver of its own fabric, using DNA as an instrument of transmission. It sculpts itself according to its own inner sense of purpose, which it inherited ultimately—like all of us—from those first autocatalytic cells: the drive to resist entropy and generate a temporary vortex of self-created order in the universe. In the words of philosopher of biology Andreas Weber, “Everything that lives wants more of life. Organisms are beings whose own existence means something to them.”

This implies that, rather than being an aggregation of unconscious machines, life is intrinsically purposive. In recent decades, carefully designed scientific studies have revealed the deep intelligence throughout the natural world employed by organisms as they fulfil their purpose of self-generation. The inner life of a plant, biologists have discovered, is a rich plethora of complex experience. Plants have their own versions of our five senses, as well as up to fifteen other ways of sensing their environment for which we don’t have analogues. Plants act intentionally and purposefully: they have memories and learn, they communicate with each other, and can even allocate resources as a community through what biologist Suzanne Simard calls the “wood-wide web” of mycorrhizal fungi linking their roots together underground.

Extensive studies now point to the profound realization that every animal with a nervous system is likely to have some sort of subjective experience driven by feelings that, at the deepest level, are shared by all of us. Bees have been shown to feel anxious when their hives are shaken. Fish will make trade-offs between hunger and pain, avoiding part of an aquarium where they’re likely to get an electric shock, even if that’s where the food is—until they get so hungry that they’re willing to take a risk. Octopuses, one of the earliest groups to evolve separately from other animals about 600 million years ago, live predominantly solitary lives, but just like humans, get cozy with others when given a dose of the “love-drug” MDMA.

The ideology of human supremacy

As we confront the existential crises of the twenty-first century, the mechanistic thinking that brought us to this place may be driving us headlong toward catastrophe. As each new global problem appears, attention gets focused on short-term, mechanistic solutions, rather than probing deeper systemic causation. In response to the worldwide collapse of butterfly and bee populations, for example, some researchers have designed tiny airborne drones to pollinate trees as artificial substitutes for their disappearing natural pollinators.

As the stakes get higher through this century, the dangers arising from this mechanistic metaphor of nature will only become more harrowing. Already, in response to the acceleration of climate breakdown, the techno-dystopian idea of geoengineering is becoming increasingly acceptable. Following Tillerson’s misconceived logic, rather than disrupt the fossil fuel-based growth economy, policymakers are beginning to seriously countenance treating the Earth as a gigantic machine that needs fixing, and developing massive engineering projects to tinker with the global climate.

Given the innumerable nonlinear feedback loops that generate our planet’s complex living systems, the law of unintended consequences looms menacingly large. The eerily named field of “solar radiation management”, for example, which has received significant financing from Bill Gates, envisages spraying particles into the stratosphere to cool the Earth by reflecting the Sun’s rays back into space. The risks are enormous, such as causing extreme shifts in precipitation around the world and exacerbating damage we’ve already done to the ozone layer. Additionally, once begun, it could never be stopped without immediate catastrophic rebound heating; it would further increase ocean acidification; and would likely turn the blue sky into a perpetual white haze. These types of feedback effects, arising from the innumerable nonlinear dynamic interdependencies of Earth’s complex systems, get marginalized by a worldview that ultimately sees our planet as a machine requiring a quick fix.

Further, there are deep moral issues that arise from confronting the inherent subjectivity of the natural world. Ever since the Scientific Revolution, the root metaphor of nature as a machine has infiltrated Western culture, inducing people to view the living Earth as a resource for humans to exploit without regard for its intrinsic value. Ecological philosopher Eileen Crist describes this as human supremacy, pointing out that seeing nature as a “resource” permits anything to be done to the Earth with no moral misgivings. Fish get reclassified as “fisheries,” and farm animals as “livestock”—living creatures become mere assets to be exploited for profit. Ultimately, it is the ideology of human supremacy that allows us to blow up mountaintops for coal, turn vibrant rainforest into monocropped wastelands, and trawl millions of miles of ocean floor with nets that scoop up everything that moves.

Once we recognize that other animals with a nervous system are not machines, as Descartes proposed, but likely experience subjective feelings similar to humans, we must also reckon with the unsettling moral implications of factory farming. The stark reality is that around the world, cows, chicken, and pigs are enslaved, tortured, and mercilessly slaughtered merely for human convenience. This systematic torment administered in the name of humanity to over 70 billion animals a year—each one a sentient creature with a nervous system as capable of registering excruciating pain as you or I—quite possibly represents the greatest cataclysm of suffering that life on Earth has ever experienced.

The “quantum jazz” of life

What, then, are metaphors of life that more accurately reflect the findings of biology—and might have the adaptive consequence of influencing our civilization to behave with more reverence toward our nonliving relatives on this beleaguered planet which is our only home?

Frequently, when cell biologists describe the mind-boggling complexity of their subject, they turn to music as a core metaphor. Denis Noble entitled his book on cellular biology The Music of Life, depicting it as “a symphony.” Ursula Goodenough describes patterns of gene expression as “melodies and harmonies.” While this metaphor rings truer than nature as a machine, it has its own limitations: a symphony is, after all, a piece of music written by a composer, with a conductor directing how each note should be played. The awesome quality of nature’s music arises from the fact that it is self-organized. There is no outside agent telling each cell what to do.

Perhaps a more illustrative metaphor would be a dance. Cell biologists increasingly refer to their findings in terms of “choreography,” and philosopher of biology Evan Thompson writes vividly how an organism and its environment relate to each other “like two partners in a dance who bring forth each other’s movements.”

Another compelling metaphor is an improvisational jazz ensemble, where a self-organized group of musicians spontaneously creates fresh melodies from a core harmonic theme, riffing off each other’s creativity in a similar way to how evolution generates complex ecosystems. Geneticist Mae-Wan Ho captures this idea with her portrayal of life as “quantum jazz,” describing it as “an incredible hive of activity at every level of magnification in the organism . . . locally appearing as though completely chaotic, and yet perfectly coordinated as a whole.”

What might our world look if we saw ourselves as participating in a coherent ensemble with all sentient beings interweaving together to collectively reverse entropy on Earth? Perhaps we might begin to see humanity’s role, not to re-engineer a broken planet for further exploitation, but to attune with the rest of life’s abundance, and ensure that our own actions harmonize with the Earth’s ecological rhythms. In the profound words of 20th century humanitarian Albert Schweitzer, “I am life that wills to live, in the midst of life that wills to live.” How, we may ask, might our future trajectory change if we were to reconstruct our civilization on this basis?

Jeremy Lent is an author and speaker whose work investigates the underlying causes of our civilization’s existential crisis, and explores pathways toward a life-affirming future. This article contains excerpts from his recently published book, The Web of Meaning: Integrating Science and Traditional Wisdom to Find Our Place in the Universe.

I’m delighted to announce that my book,

I’m delighted to announce that my book,