As civilization faces an existential crisis, our leaders demonstrate their inability to respond. Theory of change shows that now is the time for radically new ideas to transform society before it’s too late.

Of all the terrifying news bombarding us from the burning of the Amazon, perhaps the most disturbing was the offer of $22 million made by France’s President Emmanuel Macron and other G7 leaders to help Brazil put the fires out. Why is that? The answer can help to hone in on the true structural changes needed to avert civilizational collapse.

Scientists have publicly warned that, at the current rate of deforestation, the Amazon is getting dangerously close to a die-back scenario, after which it will be gone forever, turned into sparse savanna. Quite apart from the fact that this would be the greatest human-made ecological catastrophe in history, it would also further accelerate a climate cataclysm, as one of the world’s great carbon sinks would convert overnight to a major carbon emitter, with reinforcing feedback effects causing even more extreme global heating, ultimately threatening the continued existence of our current civilization.

Macron and the other leaders meeting in late August in Biarritz were well aware of these facts. And yet, in the face of this impending disaster, these supposed leaders of the free world, representing over half the economic wealth of all humanity, offered a paltry $22 million—less than Americans spend on popcorn in a single day. By way of context, global fossil fuel subsidies (much of it from G7 members) total roughly $5.2 trillion annually—over two hundred thousand times the amount offered to help Brazil fight the Amazon fires.

Brazil’s brutal president Bolsonaro is emerging as one of the worst perpetrators of ecocide in the modern world, but it’s difficult to criticize his immediate rejection of an amount that is, at best a pittance, at worst an insult. True to form, Donald Trump didn’t bother to turn up for the discussion on the Amazon fires, but it hardly made a difference. The ultimate message from the rest of the G7 nations was they were utterly unable, or unwilling, to lift a finger to help prevent the looming existential crisis facing our civilization.

Why Aren’t They Doing Anything?

This should not be news to anyone following the unfolding twin disasters of climate breakdown and ecological collapse. It’s easy enough to be horrified at Bolsonaro’s brazenness, encouraging lawless ranchers to burn down the Amazon rainforest to clear land for soybean plantations and cattle grazing, but the subtler, and far more powerful, forces driving us to the precipice come from the Global North. It’s the global appetite for beef consumption that lures Brazil’s farmers to devastate one of the world’s most precious treasure troves of biodiversity. It’s the global demand for fossil fuels that rewards oil companies for the wanton destruction of pristine forest.

There is no clearer evidence of the Global North’s hypocrisy in this regard than the sad story of Ecuador’s Yasuní initiative. In 2007, Ecuador’s president, Rafael Correa proposed an indefinite ban on oil exploration in the pristine Yasuní National Park—representing 20% of the nation’s oil deposits—as long as the developed world would contribute half the cost that Ecuador faced by foregoing oil revenues. Initially, wealthier countries announced their support for this visionary plan, and a UN-administered fund was established. However, after six years of strenuous effort, Ecuador had received just 0.37% of the fund’s target. With sorrow, the government announced it would allow oil drilling to begin.

The simple lesson is that our global leaders currently have no intention to make even the feeblest steps toward changing the underlying drivers of our society’s self-destruction. They are merely marching in lockstep to the true forces propelling our global civilization: the transnational corporations that control virtually every aspect of economic activity. These, in turn, are driven by the requirement to relentlessly increase shareholder value at all cost, which they do by turning the living Earth into a resource for reckless exploitation, and conditioning people everywhere to become zombie consumers.

This global system of unregulated neoliberal capitalism was unleashed in full fury by the free market credo of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s, and has since become the underlying substrate of our politics, culture, and economics. The system’s true cruelty, destructiveness, and suicidal negligence are now showing themselves in the unraveling of our world order, as manifested in the most extreme inequality in history, the polarized intolerance of political discourse, the rise in desperate climate refugees, and a natural world that is burning up, melting down, and has already lost most of its nonhuman inhabitants.

How Change Happens

Studies of past civilizations show that all the major criteria that predictably lead to civilizational collapse are currently confronting us: climate change, environmental degradation, rising inequality, and escalation in societal complexity. As societies begin to unravel, they have to keep running faster and faster to remain in the same place, until finally an unexpected shock arrives and the whole edifice disintegrates.

It’s a terrifying scenario, but understanding its dynamics enables us to have greater impact on what actually happens than we may realize. Scientists have studied the life cycles of all kinds of complex systems—ranging in size from single cells to vast ecosystems, and back in time all the way to earlier mass extinctions—and have derived a general theory of change called the Adaptive Cycle model. This model works equally well for human systems such as industries, markets, and societies. As a rule, complex systems pass through a life cycle consisting of four phases: a rapid growth phase when those employing innovative strategies can exploit new opportunities; a more stable conservation phase, dominated by long-established relationships that gradually become increasingly brittle and resistant to change; a release phase, which might be a collapse, characterized by chaos and uncertainty; and finally, a reorganization phase during which small, seemingly insignificant forces can drastically change the future of the new cycle.

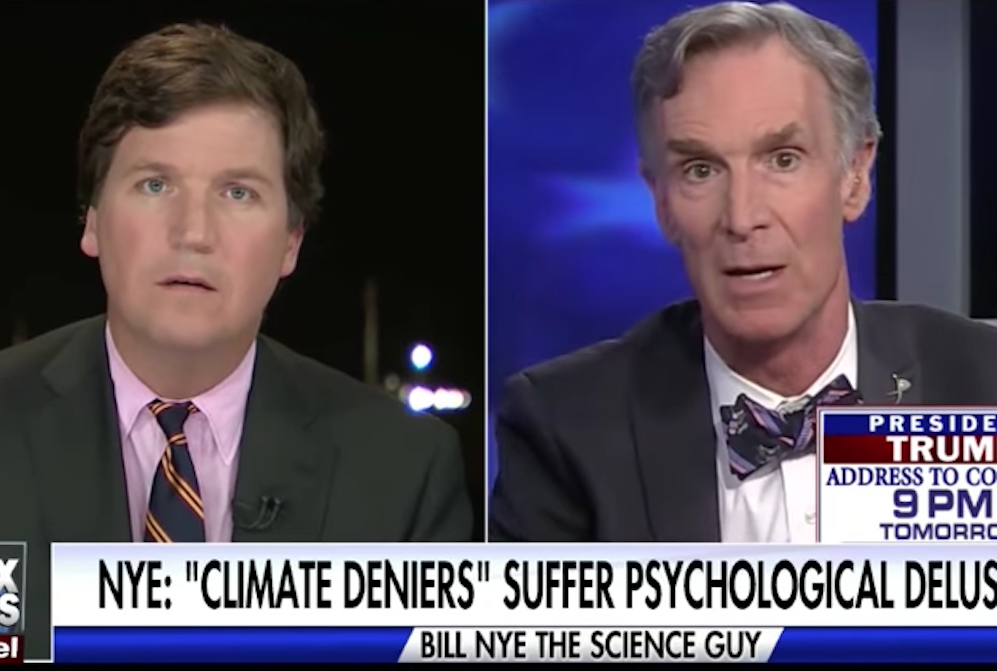

Right now, many people might agree that our global civilization is at the late stage of its conservation phase, and in many segments, it feels like it’s already entering the chaotic release phase. This is a crucially important moment in the system’s life cycle for those who wish to change the predominant order. As long as the conservation phase remains stable, new ideas can barely make an impact on the established, tightly connected dominant ecosystem of power, relationships, and narrative. However, as things begin to unravel, we see increasing numbers of people begin to question foundational elements of neoliberal capitalism: an economy based on perpetual growth, seeing nature as a resource to plunder, and the pursuit of material wealth as paramount.

This is the time when new ideas can have an outsize impact. Innovative policy ideas previously considered unthinkable begin to enter the domain of mainstream political discourse (known as the Overton window). We see signs of this in the United States in the form of the Green New Deal, or Elizabeth Warren’s plan to hold corporations accountable. We also see it, disturbingly, in dark political forces such as the UK Brexit fiasco and the increasing acceptability of malevolent racist rhetoric around the world.

The stakes are always at their highest when both the economic and cultural norms of a society begin to fall apart in tandem. When Europe underwent a phase of collapse and renewal in the early twentieth-century, after the devastation of World War I, it became fertile terrain for the hate-filled ideologies of Fascism and Nazism that led to the dark abyss of genocide and concentration camps. The ensuing catastrophe of World War II led to another collapse and renewal cycle, this one providing the platform for the current globalized world order that is now entering the final stages of its own life cycle.

Shifting the Overton Window

What will emerge from the current slide into ecological and political chaos? Will the twin dark forces of billionaires’ wealth and xenophobic nationalism lead us into another abyss? Or can we somehow transform our global society peacefully into a fundamentally different system—one that affirms life rather than material wealth as paramount?

One thing is clear: the visionary ideas that will determine the shape of our future will not be based on incremental thinking within the confines of our current system. Achieving needed reforms within the current global power structure is a worthwhile goal, but is not sufficient to lead humanity to a thriving future. For that, we need bold, new ways of structuring our civilization, and of rethinking the human relationship with the natural world. We need to be ready to restructure the legal basis of corporations to serve humanity rather than faceless shareholders. We need global laws that force ecocidal thugs like Bolsonaro to face justice for their crimes against nature.

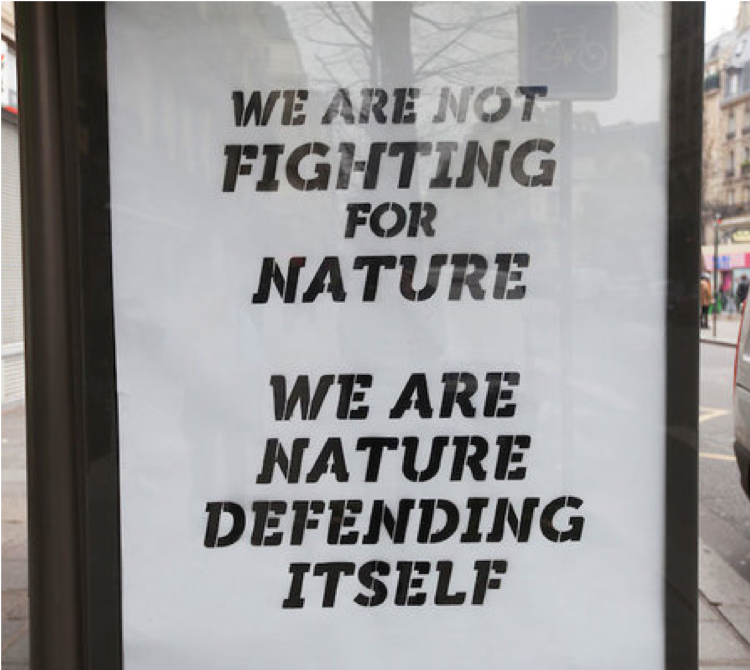

You won’t currently find these new ways of thinking in the mainstream media, nor in the speeches of politicians trying to get elected. But you will find them in the streets. You’ll find them in the courage of a Greta Thunberg: a solitary teenage girl sitting for days in front of her parliament, who has since inspired millions of schoolchildren to strike for their future. You’ll find them in the demands of the Extinction Rebellion movement, which calls for elected leaders to tell the truth about our ecological and climate crisis, and to empower citizen’s assemblies to develop truly meaningful solutions.

The changes needed for a hopeful future will not come about from our current leaders, which is why all of us who care for future generations and for the richness of life on Earth, must take the leadership role in their place. We need to shift the Overton window until it centers on the real issues that will determine our future. On September 20, three days before the UN Climate Summit in New York, millions of young people and adults will participate in a Global Climate Strike, taking to the streets to demand the transformative action that’s necessary to stave off ecological and civilizational collapse. Actions are being planned in over a thousand cities around the world, for what may turn out to be the single biggest coordinated grassroots global demonstration in history.

The stakes have never been higher: the threat of catastrophe never more dreadful; and the path to societal transformation never so apparent. Which future are you steering us to? There’s no opting out: anyone with an inkling of what’s happening around the world, but who does nothing about it, is implicitly adding their momentum toward the abyss of collapse. I hope you join us on September 20 in helping steer our civilization toward a path of future flourishing.

Jeremy Lent is author of The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity’s Search for Meaning, which investigates how different cultures have made sense of the universe and how their underlying values have changed the course of history. He is founder of the nonprofit Liology Institute, dedicated to fostering a sustainable worldview. For more information visit jeremylent.com.