The re-election of Donald Trump to the US Presidency will have global implications for decades to come. This article identifies key underlying drivers that led to this event, explores the potential landscape of the next few years, and sheds light on a positive way forward. Out of the approaching turbulence, there remains a possibility of life-affirming potentialities that can be nurtured and brought to fruition.

A political cataclysm has taken place in the United States that will have global implications for decades to come. A majority of Americans has chosen to entrust their nation to an authoritarian self-promoter and adjudicated sexual molester who has vowed to be a “dictator” on day one. The election of Donald Trump to head the world’s most powerful country, with minimal institutional or legal restraints on his power, could turn out to be one of the most momentous events in the history of the modern world.

How did Americans willingly take this path? What is it likely to mean? And what is the most skillful response? This article identifies key underlying drivers that led to this event, explores the potential landscape of the next few years, and sheds light on a positive way forward—for each of us as individuals and for our collective future. Out of the approaching turbulence, there remains a possibility that life-affirming potentialities may be generated that can be nurtured and brought to fruition.

Primary Underlying Causes

Most political pundits analyzing the election have been focusing on the wrong questions. In the end, it doesn’t matter why the swing states went for Trump rather than Harris. The real question we need to ask is why roughly half the citizens of the United States could have even considered voting for an inveterate liar and demagogue in the first place. Only by investigating that question can we begin to identify a potential way out of the quagmire.

I see two primary underlying and interlinked causes for this political cataclysm.

The first is the anguish and alienation caused by the ravages of neoliberalism and the impotence of the Democratic party to offer any meaningful alternative.

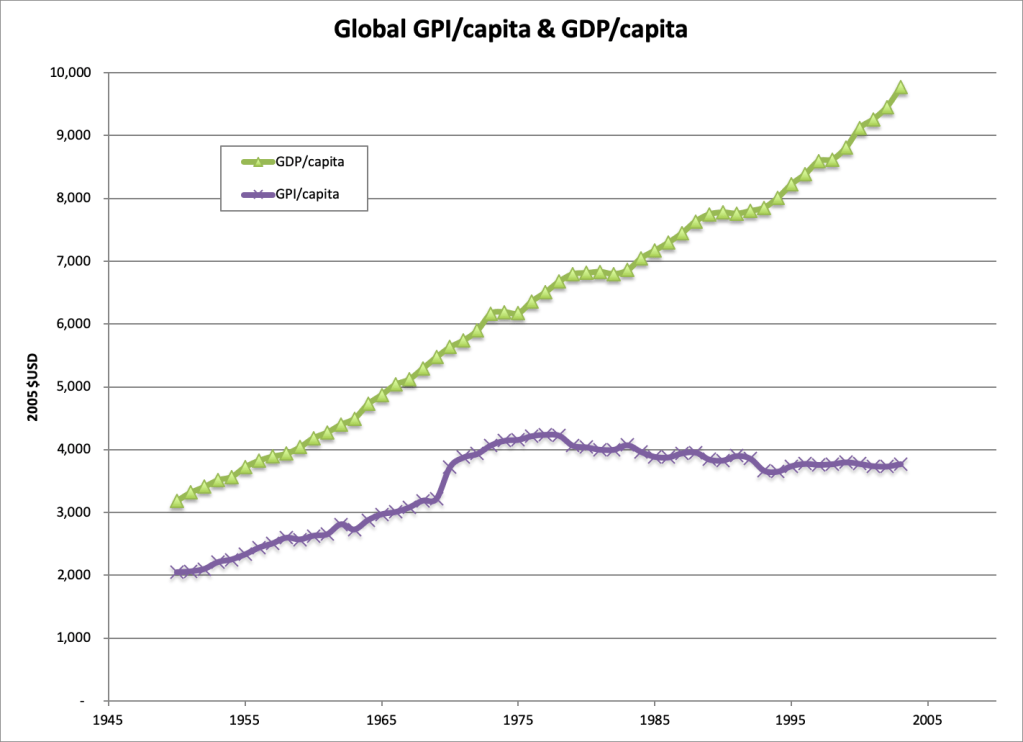

Neoliberalism is an ideology that first emerged in the 1970s and has since become the de facto governing doctrine of virtually every aspect of human endeavor, infiltrating its core beliefs into areas as wide-ranging as politics, finance, culture, education, technology, and agriculture. It holds that humans are individualistic, selfish, calculating materialists, and because of this, unrestrained free-market capitalism provides the best framework for every kind of human activity. These precepts lead to a fundamental belief in the value of unrestrained competition, with free markets, free trade, and minimal rules or restrictions. Wealth is seen as the ultimate measure of success, as manifested in personal riches, business profitability, or a nation’s gross domestic product. Inequality, therefore, far from being pernicious, is a sign of a society’s health, because it permits those who are most accomplished to be maximally rewarded.

Neoliberal ideas were first implemented as national policy in the 1980s by Republican President Ronald Reagan, along with Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in the UK. But the crucial turning point came several years later with the abject acceptance of this ideology by Democratic President Bill Clinton along with Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair in the UK. From this point on, the Democrats no longer stood for the common people, but instead became primarily another instrument of corporate power and billionaires. In fact, it was during Bill Clinton’s presidency, between 1993 and 2001, that the income and wealth gaps between the wealthiest 1 percent and ordinary people broadened more than ever before (see the figures below).

This gaping disparity was further exacerbated by the inaction of President Obama after the 2008 financial meltdown and the consequent rise of the Occupy Movement. Instead of responding to this crisis by initiating a transformative Green New Deal, Obama doubled down on neoliberal ideology, coordinating the global establishment to spend $1 trillion dollars to bail out the banks with taxpayers’ money without demanding any meaningful reform in return.

Bernie Sanders, in 2016, offered a brief glimpse of an alternative program in his campaign for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination, calling for a “political revolution” and rejecting donations above $2,700, but he was shut out by the Democratic establishment. This was the pivotal moment that led to the current predicament. If we could re-run the reel of history with Bernie as Democratic presidential candidate in 2016, there is an excellent chance he would have won the election by offering a real path forward to common people, and we could now be living in a period of positive transformative change.

Instead, the Democrats have offered nothing other than “business as usual,” leaving vast numbers of disaffected Americans to channel their rage and resentment elsewhere: right into the hands of a rising authoritarian movement only too ready to stoke their anger with constructed “culture wars” fueled by misogyny and racism. Ordinary Americans are right to feel betrayed by the Democratic party. In choosing between one party that supports the status quo and another that calls for the wrecking ball, it’s not surprising that large numbers of struggling voters chose a candidate who claims he will demolish the system that has immiserated them.

The second interrelated reason is the rise in epistemic chaos generated by social media and weaponized by Elon Musk and others. The public sphere, which until recently has been maintained by a confluence of traditional media, academic institutions, news organizations, governments, and the public itself, has now been privatized by the large-scale algorithmic curation of the major platforms, which coordinate and steer the opinions and actions of billions of people.

Their concern is not to facilitate wise collective decision-making, but to increase advertising revenues by maximizing engagement. Since false news stories have been shown to reach six times as many people as true stories, these are emphasized by the selection algorithms. As we’ve seen, politically motivated special interest groups use the platforms to intensify polarization by spreading malicious propaganda, as exemplified by Musk’s takeover of Twitter to turn it into his own personal megaphone.

The shared sense-making that is fundamental to a healthy society has been systematically shredded, leading to widespread epistemic chaos fraught with bizarre conspiracy theories adopted as facts by an increasingly disoriented population.

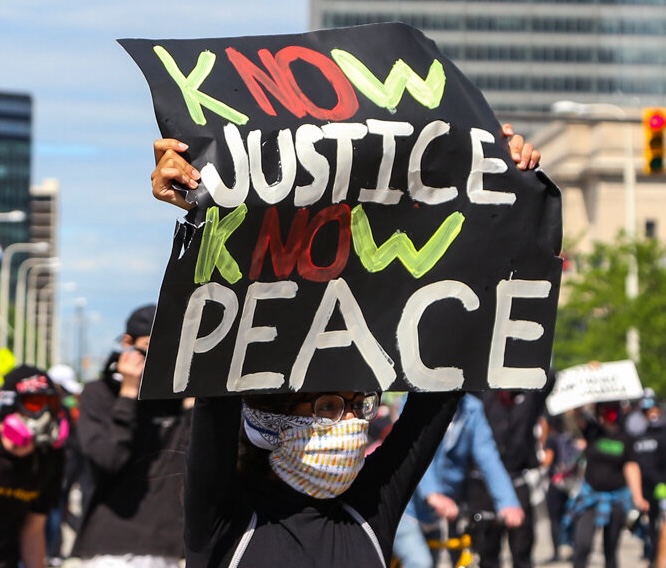

It is the linkage between these two dynamics that led inexorably to the election of Trump. Americans know intuitively that the economic system has unfairly deprived them while magnifying the wealth of the elites. However, in the epistemic chaos of the public sphere, their minds have been systematically manipulated by Musk, Fox News, and other right-wing social media sites to believe false stories about the cause of their distress. Instead of aiming their anger at the elite echelon of centimillionaires and billionaires, corporations, and banks sucking the nation’s wealth from the common people, their rage has been misdirected toward the most vulnerable populations—racial and ethnic minorities, undocumented migrant workers and transgender people—who have played no part in their immiseration.

“The people who make $700 an hour have convinced the people who make $25 an hour that the problem is the people who make $7.50 an hour.” – @Jesse-v7h

What to Expect in the Next Few Years

The election of Donald Trump will not, however, alleviate the misery of those who turned to him. On the contrary, Trump—himself a billionaire—is stacking up the wealthiest administration in history, with a team containing 13 billionaires with a net worth of more than $350 billion dedicated to cutting spending on public services used by the poor and vulnerable, and shredding regulations that might block their pursuit of even vaster wealth.

With control of Congress, and the majority of the Supreme Court as his lackeys, Trump has no meaningful institutional restraints on his power. No-one can predict exactly how the new regime in Washington will play out, but the public statements made by Trump and his appointees indicate that we are entering a period when virtually every democratic norm will be overturned. Trump has repeatedly spoken like a Fascist demagogue dehumanizing his enemies, openly telling supporters at a rally that he would “root out the communists, Marxists, fascists and the radical left thugs that live like vermin within the confines of our country that lie and steal and cheat on elections.” He has vowed, on his first day, to pardon rioters imprisoned after the January 6, 2021 insurrection and begin mass deportation for the estimated 11 million people living in the US without legal immigration documents.

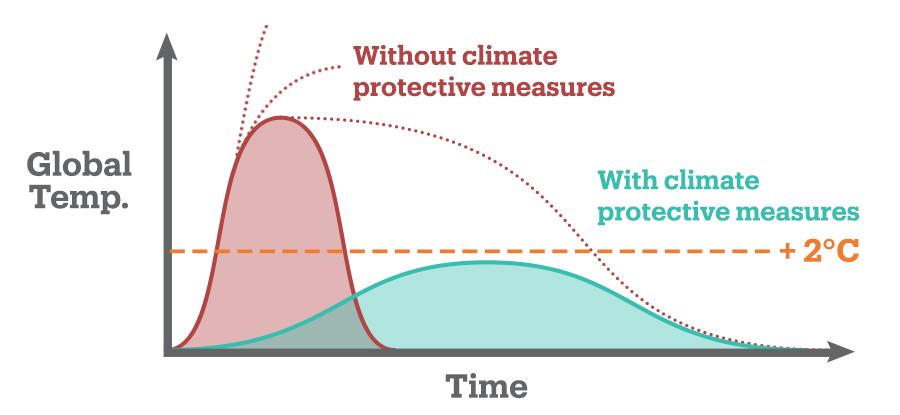

Based on the policies proposed by those that Trump has already selected for his administration, we should expect legislation criminalizing abortion care and restricting access so widely as to become an effective nationwide abortion ban, and a campaign of terror leading to millions of innocent undocumented migrants locked up in detention camps. Internationally, in addition to the possibility of prohibitive tariffs raising the cost of living for ordinary people, we can expect the US to pull out of the UN-administered climate COP process which is already on life-support, and European nations will face renewed threats from Trump about the US pulling out of NATO, further empowering Putin to threaten Europe militarily.

More broadly, we must expect an attack on democracy itself, including massive lawsuits against media outlets (which have already begun) leading to a virtual shutting down of free speech, widespread banning in schools and libraries of books with progressive perspectives—following the model set by Ron DeSantis in Florida where it’s illegal to teach critical race theory—and the threat of violence everywhere as right-wing extremist armed gangs learn they can act with impunity. Culturally, the ascent to power of leaders directly associated with misogyny, racism, violence, corruption, and cruelty will have far-flung reverberations, further elevating these pernicious values and behaviors as cultural norms.

In his first administration, Trump’s authoritarian tendencies were largely checked by legal challenges, institutional barriers, and his own chaotic mismanagement. However, in the past eight years, a focused group of extremists has developed a comprehensive plan for the overthrow of the administrative infrastructure that the vast majority of Americans rely on, laid out in terrifying detail in the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025, which will be now be used as a blueprint for the new administration. In line with Project 2025, Trump’s appointees—some of whom were its key contributors—have explicitly called for the elimination, dismantling, or severe downsizing of agencies such as the Department of Education, the EPA, the Federal Trade Commission, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the FDA, the IRS, and the NIH.

Democracy in the United States has long been tarnished by the power of money and corruption. While studies looking back over decades have demonstrated that legislation is passed primarily for the benefit of corporations and wealthy elites, their interests have at least been held in check by an assemblage of laws attempting to regulate some of the worst excesses of capitalism. That era is now at an end. The US is becoming a consummate plutocracy—government by the wealthy for the wealthy—in which the very idea of “conflicts of interest” will come to be seen as a quaint relic of a bygone age, as the nation enters an era in which the primary objective of its rulers is to flagrantly expand further their own wealth and power.

There is, moreover, every reason to expect that the Justice Department and FBI will be subverted to become instruments of Trump’s personal vendettas. His plans for personal retribution have invoked a wide array of his political opponents including Nancy Pelosi, Kamala Harris, Adam Schiff, Liz Cheney, former FBI director James Comey, and Barak Obama, many of whom he has claimed should be “impeached and prosecuted.” In the case of former Joint Chief of Staff Mark Milley, who earned Trump’s ire by describing him as “Fascist to the core,” he has even floated the idea of executing him for treason.

Since the Supreme Court granted Trump presumptive immunity in July 2024 for his official acts, there is no realistic constraint to prevent Trump asserting dictatorial powers in the coming months, if he should choose it. Political analysts have looked to historical precedents such as Orban in Hungary, Duterte in the Philippines, or Hitler in Germany, to try to predict how Trump might seize full control. It is not inconceivable that, like Hitler, Trump could take advantage of a “Reichstag Fire” opportunity to impose martial law which could suspend civil liberties, impose curfews and restriction of movement, replace the civilian justice system with military justice, and give him power to deploy military force on US territory.

As Democrats attempt to regroup and hope that the mid-term elections of 2026 might give them the possibility of regaining control of Congress, it is not unreasonable to ask whether there will actually be authentic mid-term elections by that time.

Charting a Way Forward

As a teenager growing up in England in the 1970s and becoming aware of the horror that had afflicted the world only a few decades earlier, I felt deeply grateful for inhabiting a world that, flawed as it was, operated, at least in principle, according to a set of moral norms that eschewed racism, genocide, and structural cruelty. I wondered how people felt in the 1930s as they saw the darkness of such forces encroaching.

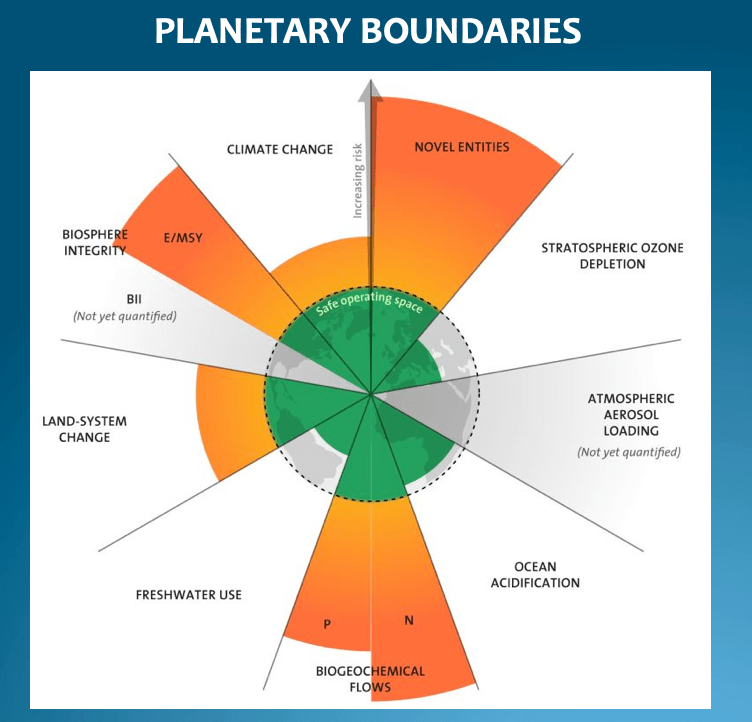

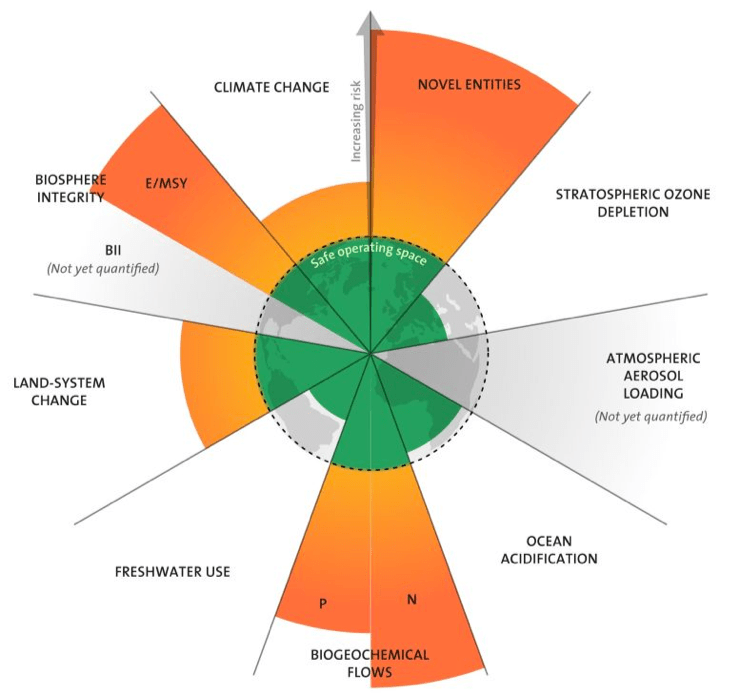

We no longer need to wonder about that. The re-election of Trump to the presidency of the world’s most powerful country is a fateful step toward an abyss into which the world system has already been inexorably slipping. Humanity is entering a period of epochal change. The dominant civilization is on a trajectory of climate breakdown, ecological disaster, and unconscionable levels of inequality—potentially leading to a collapse of the entire world system in the decades to come. The rise in authoritarianism around the world is an expected phenomenon as people recognize the system is failing them and turn to those who stoke their deepest fears with anger and resentment.

This is not, however, cause for despair. While the future has never appeared bleaker, this does not mean that anyone should give up on the potential of a brighter path forward. Far from it. As darkness envelops our world, the remaining beams of light become even more crucial to keep us oriented. As the current world system unravels, this opens up the possibility—remote as it might appear right now—to re-weave it into an entirely different form of organization.

For those of us who live in the US, and who have any kind of cultural, racial, or economic privilege, it will be crucial to attune to the needs of those most at risk from the institutional violence that is at hand. There has never been a time when inner resources arising from spiritual practice are called for more than now. After an initial period of grief, there is an imperative for us to cultivate all the love and compassion available within ourselves and offer that in abundance to those around us. Let our response to what unfolds be driven by compassion manifested in skillful action.

What does skillful action entail? Recognizing the forces that have led to this cataclysm allows us to orient ourselves to the behaviors that can counteract them. Here are some principles that might help to guide us.

Stay true to your core values

These are disorienting times, and those who wield authoritarian rule maintain their power by keeping their potential opponents off-balance. When greed and ruthlessness prevail, it is easy to lose faith in fundamental human qualities such as kindness, respect, solidarity, and hope. However, this is exactly when those qualities become most important. Hope, in the words of Czech dissident Václav Havel—who spent years as a political prisoner before becoming his country’s president—is “a state of mind, not a state of the world.” It is a “deep orientation of the human soul that can be held at the darkest times . . . an ability to work for something because it is good, not just because it stands a chance to succeed.” That is what we must all cultivate.

Stay grounded factually

The epistemic chaos created by social media, and weaponized by Musk and others, can only be withstood by a commitment to careful discernment about what is happening around us. Consider the sources of the information you obtain. Obtain your news from media such as The Guardian which have a proven track record of veracity. When you encounter an unexpected news item from an acquaintance or on social media, check alternative sources to validate it before passing it on to others.

Don’t exacerbate polarization

Since fascism thrives on polarization, it is crucial to avoid further exacerbating the “othering” of those with whom we disagree. We can forcefully act against the ideas and behaviors that cause harm while maintaining a respect for the inherent dignity of all our fellow humans. Beneath the words of those we might consider our political opponents, there exists a sensitive soul—perhaps hardened through years of undeserved suffering—that desires to be seen and cherished. It is from a shared basis of core human values that political healing has the potential to emerge.

Don’t succumb to anticipatory obedience

Historian Timothy Snyder, who has studied the rise of authoritarianism in the twentieth century, explains that much of power accruing to authoritarian regimes is surrendered in advance. “Most of the power of authoritarianism is freely given” he writes. “In times like these, individuals think ahead about what a more repressive government will want, and then offer themselves without being asked. A citizen who adapts in this way is teaching power what it can do.” There are, of course, times when it’s prudent not to speak your mind. But whenever you are faced with that choice, keep this precept in mind, and consider what the courageous course might be.

Connect with others whom you trust

Whatever difficult feelings arise in you, and whatever you’d like to do to help those in need, you can be sure there are others around with similar experiences and intentions. Seek them out and participate in creating a shared community of care. When we truly open our hearts to each other, there is no burden too heavy for us to carry together, there is no pain too deep for us to hold in each other’s arms. And it is together that we can find the most skillful way to respond to the most pressing needs around us.

Help to develop alternatives

In 1980, as Margaret Thatcher was consolidating her power in the UK, she uttered the ominous statement “There is no alternative.” For four and a half decades, most mainstream politicians have acted as if they believed she was right. The only way for society to be structured, it’s been assumed, is in the form of growth-based consumer capitalism—a system in which corporate profits ultimately drive the decisions that affect the lives of everyone on the planet, the health of the living Earth, and the destiny of future generations. This false belief forms the basis of the consensus trance that has now given rise to an authoritarian takeover of much of our world. People should not have to choose between corporate-controlled neoliberalism and corporate-backed fascism—between a hypocritical oligarchy and a flagrant plutocracy.

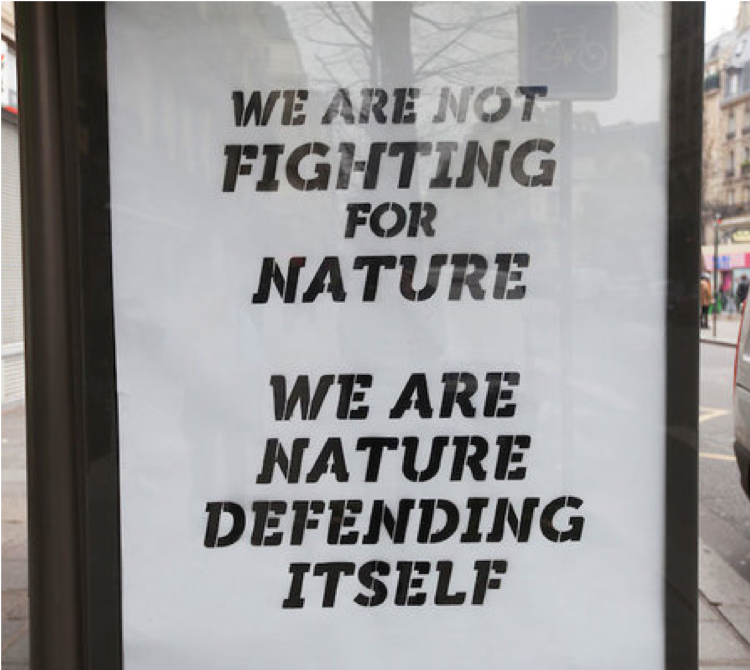

It is time to recognize that there is an alternative to this system of devastation. There is, in fact, a different way forward, an opportunity to reclaim our future, but it requires something that goes even beyond Bernie’s “political revolution”—it requires a complete systemic transformation to a different kind of civilization, one that replaces extraction and exploitation with a system that sets the conditions for all beings to thrive on a regenerated Earth.

Around the world, changemakers, community organizers, and researchers are working assiduously laying down pathways toward this life-affirming future, which is increasingly being called an “Ecocivilization.” While they may not always see themselves as part of a larger movement, they’re driven by a shared set of core human imperatives to care for others around them, nurture the living Earth, and strive to leave a healthy world for future generations to inherit.

In every aspect of our world system, these alternative futures present themselves. Advanced technology can be reconfigured to empower all of us rather than a few mega-corporations, cities can be redesigned to promote wellbeing rather than consumerism and traffic jams, and even democracy can be reconceived so that regular citizens, rather than wealthy oligarchs, can thoughtfully determine the best policies for society. We can—and must—envisage a world where corporations have been legally restructured to work for people and the planet rather than merely profits, where there is a cap on the wealth of billionaires, and where enforceable Rights of Nature legislation looks out for the welfare of the other sentient beings with whom we share our world.

The disaffected voters who chose Donald Trump’s wrecking ball over the paltry reforms offered by the Democrats felt something deep in their gut: The system isn’t broken—it’s doing exactly what it was intended to do. They are right about that. But rather than demolish the system for the benefit of the plutocrats, it can be transformed and reconstructed into a world that works for all.

This is my invitation to all those who feel the suffering around them and who want to work generatively with others to investigate what’s possible for a transformed world. Act as a beacon in the dark. Join others in taking skillful, compassionate action to support those most in need. Seek out, learn about, and help to build life-affirming alternatives. Let us collectively offer those around us a loving, nurturing container of sense-making that can attract those who are feeling despair and enjoin them to help us lay down a pathway together to a brighter future.

Jeremy Lent is an author and speaker whose work investigates the underlying causes of our civilization’s existential crisis, and explores pathways toward a life-affirming future. In addition to his award-winning books The Patterning Instinct and The Web of Meaning, he is founder of the online community, the Deep Transformation Network. His upcoming book, Ecocivilization: How We Can Reclaim Our Future, will be published by Melville House in 2026.