The explosive rise in the power of AI presents humanity with an existential risk. To counter that risk, and potentially redirect our civilization’s trajectory, we need a more integrated understanding of the nature of human intelligence and the fundamental requirements for human flourishing.

The recent explosion in the stunning power of artificial intelligence is likely to transform virtually every domain of human life in the near future, with effects that no-one can yet predict.

The breakneck rate at which AI is developing is such that its potential impact is almost impossible to grasp. As Tristan Harris and Aza Raskin, co-founders of the Center for Humane Technology, demonstrate in their landmark presentation, The AI Dilemma, AI accomplishments are beginning to read like science fiction. After just three seconds of hearing a human voice, for example, an AI system can autocomplete the sentence being spoken with a voice so perfectly matched that no-one can distinguish it from the real thing. AI linked with fMRI brain imaging technology, they show us, can now reconstruct what a person’s brain is thinking and represent it accurately as an image.

AI models are beginning to exhibit emergent capabilities their programmers didn’t program into them. An AI model trained to answer questions in English can suddenly understand and answer questions in Persian without being trained in the language—and no-one, not even its programmers, knows why. ChatGPT, to the surprise of its own programmers, was discovered to have trained itself in research-level chemistry even though that wasn’t part of its targeted training data.

Many of these developments have been unfolding at a time scale no longer measured in months and years, but in weeks and days. Experts are comparing the significance of the AI phenomenon to the invention of the nuclear bomb, except with a spine-chilling difference: whereas the magnitude of the nuclear threat could only increase at the pace of scientists’ own capabilities, AI is becoming increasingly capable of learning how to make itself more powerful. In recent examples, AI models have learned to generate their own training data to self-improve, and to edit sections of code so as to make the code work at more than double the speed. AI capabilities have already been expanding at an exponential rate, largely as a result of the distributed network effects of programmers building on each other’s breakthroughs. But given these recent developments, experts are forecasting future improvements at a double exponential rate, which begins to look on a graph like a vertical line of potentiality exploding upward.

The term generally used to describe this phenomenon, which heretofore has been a hypothetical thought experiment, is a Singularity. Back in 1965, at the outset of the computer age, British mathematician, I. J. Good, first described this powerful and unsettling vision. “Let an ultraintelligent machine,” he wrote, “be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an ‘intelligence explosion’, and the intelligence of man would be left far behind. Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make.”[1]

Nearly six decades after it was first conceived, the Singularity has mutated from a theoretical speculation to an urgent existential concern. Of course, it is easy to enumerate the myriad potential benefits of an ultraintelligent computer: discoveries of cures to debilitating diseases; ultra-sophisticated, multifaceted automation to replace human drudgery; technological solutions to humanity’s most pressing problems. Conversely, observers are also pointing out the dangerously disruptive potential of advanced AI on a world already fraying at the seams: the risk of deep fakes and automated bots polarizing society even further; personalized AI assistants exploiting people for profit and exacerbating the epidemic of social isolation; and greater centralization of power to a few mega-corporations, to name but a few of the primary issues. But even beyond these serious concerns, leading AI experts are warning that an advanced artificial general intelligence (“AGI”) is likely to represent a grave threat, not just to human civilization, but to the very existence of humanity and the continuation of life on Earth.

The alignment problem

At the root of this profound risk is something known as the alignment problem. What would happen, we must ask, if a superhuman intelligence wants to achieve some goal that’s out of alignment with the conditions required for human welfare—or for that matter, the survival of life itself on Earth? This misalignment could simply be the result of misguided human programming. Prominent futurist Nick Bostrom gives an example of a superintelligence designed with the goal of manufacturing paperclips that transforms the entire Earth into a gigantic paperclip manufacturing facility.

It’s also quite conceivable that a superintelligent AI could develop its own goal orientation, which would be highly likely to be misaligned with human flourishing. The AI might not see humans as an enemy to be eliminated, but we could simply become collateral damage to its own purposes, in the same way that orangutans, mountain gorillas, and a myriad other species face extinction as the result of human activity. For example, a superintelligence might want to optimize the Earth’s atmosphere for its own processing speed, leading to a biosphere that could no longer sustain life.

As superintelligence moves from a thought experiment to an urgently looming existential crisis, many leading analysts who have studied these issues for decades are extraordinarily terrified and trying to raise the alarm before it’s too late. MIT professor Max Tegmark, a highly respected physicist and president of the Future of Life Institute, considers this our “Don’t Look Up” moment, referring to the satirical movie in which an asteroid threatens life on Earth with extinction, but a plan to save the planet is waylaid by corporate interests and the public’s inability to turn their attention away from celebrity gossip. In an intimate podcast interview, Tegmark likens our situation to receiving a terminal cancer diagnosis for the entire human race, declaring that “there’s a pretty large chance that we’re not going to make it as humans; that there won’t be any humans on the planet in the not-too-distant future—and that makes me very sad.”

Tegmark’s fear is shared by other leading experts. Eliezer Yudkowsky, who has been working on aligning AGI since 2001 and is widely regarded as a founder of the field, points out that “a sufficiently intelligent AI won’t stay confined to computers for long. In today’s world you can email DNA strings to laboratories that will produce proteins on demand, allowing an AI initially confined to the internet to build artificial life forms or bootstrap straight to postbiological molecular manufacturing.” Yudkowsky calls for an immediate and indefinite worldwide moratorium on further AI development, enforced by coordinated international military action if necessary.

In the short-term, there are several policy proposals urged by leaders in the AI community to try to rein in some of the more obvious societal disruptions anticipated by AI’s increasingly pervasive influence. An open letter calling for a pause on further development for at least six months has over thirty thousand signatories, including many of the most prominent names in the field. Beyond a worldwide moratorium, proposals include a requirement that any AI-generated material is clearly labeled as such; a stipulation that all new AI source code is published to enable transparency; and a legal presumption that new versions of AI are unsafe unless proven otherwise, putting the burden of proof on AI developers to demonstrate its safety prior to its deployment—analogous to the legal framework used in the pharmaceutical industry.

These proposals are eminently sensible and should promptly be enacted by national governments, while a UN-sponsored international panel of AI experts should be appointed to recommend further guidelines for worldwide adoption. Ultimately, the overarching strategy of such guidelines should be to restrict the further empowerment of AI unless or until the alignment problem itself can be satisfactorily solved.

There is, however, a serious misconception seemingly shared by the vast majority of AI theorists that must be recognized and corrected for any serious progress to be made in the alignment problem. This relates to the nature of intelligence itself. Until a deeper understanding of what comprises intelligence is more widely embraced in the AI community, we are in danger, not just of failing to resolve the alignment problem, but of moving in the wrong direction in its consideration.

Conceptual and animate intelligence

When AI theorists write about intelligence, they frequently start from the presumption that there is only one form of intelligence: the kind of analytical intelligence that gets measured in an IQ test and has enabled the human species to dominate the rest of the natural world—and the type in which AI now threatens to surpass us. The AI community is not alone in this presumption—it is shared by most people in the modern world, and forms a central part of the mainstream view of what it means to be a human being. When Descartes declared “cogito ergo sum”—“I think, therefore I am”—setting the intellectual foundation for modern philosophical thought, he was giving voice to a presumption that the faculty of conceptual thought was humanity’s defining characteristic, setting humanity apart from all other living beings. Animals, according to Descartes and the majority of scientists ever since, were mere machines acting without subjectivity or thought.[2]

However, the human conceptualizing faculty, powerful as it is, is only one form of intelligence. There is another form—animate intelligence—that is an integral part of human cognition, and which we share with the rest of life on Earth.

If we understand intelligence, as it’s commonly defined, to be the ability to perceive or infer information and apply it toward adaptive behaviors, intelligence exists everywhere in the living world. It’s relatively easy to see it in high-functioning mammals such as elephants that can communicate through infrasound over hundreds of miles and perform what appear like ceremonies over the bones of dead relatives; or in cetaceans that communicate in sophisticated “languages” and are thought to “gossip” about community members that are absent.[3] But extensive animate intelligence has also been identified in plants which, in addition to their own versions of our five senses, also use up to fifteen other ways to sense their environment. Plants have elaborate internal signaling systems, utilizing the same chemicals—such as serotonin or dopamine—that act as neurotransmitters in humans; and they have been shown to act intentionally and purposefully: they have memory and learn, they communicate with each other, and can even allocate resources as a community.[4]

Animate intelligence can be discerned even at a cellular level: a single cell has thousands of sensors protruding through its outer membrane, controlling the flow of specific molecules, either pulling them in or pushing them out depending on what’s needed. Cells utilize fine-tuned signaling mechanisms to communicate with others around them, sending and receiving hundreds of signals at the same time. Each cell must be aware of itself as a self: it “knows” what is within its membrane and what is outside; it determines what molecules it needs, and which ones to discard; it knows when something within it needs fixing, and how to get it done; it determines what genes to express within its DNA, and when it’s time to divide and thus propagate itself. In the words of philosopher of biology Evan Thompson, “Where there is life there is mind.”[5]

When leading cognitive neuroscientists investigate human consciousness, they make a similar differentiation between two forms of consciousness which, like intelligence, can also be classified as conceptual and animate. For example, Nobel Prize winner Gerald Edelman distinguished between what he called primary (animate) and secondary (conceptual) consciousness, while world-renowned neuroscientist Antonio Damasio makes a similar distinction between what he calls core and higher-order consciousness. Similarly, in psychology, dual systems theory posits two forms of human cognition—intuitive and analytical—described compellingly in Daniel Kahneman’s bestseller Thinking Fast and Slow, which correspond to the animate and conceptual split within both intelligence and consciousness.[6]

Toward an integrated intelligence

An implication of this increasingly widespread recognition of the existence of both animate and conceptual intelligence is that the Cartesian conception of intelligence as solely analytical—one that’s shared by a large majority of AI theorists—is dangerously limited.

Even human conceptual intelligence has been shown to emerge from a scaffolding of animate consciousness. As demonstrated convincingly by cognitive linguist George Lakoff, the abstract ideas and concepts we use to build our theoretical models of the world actually arise from metaphors of our embodied experience of the world—high and low, in and out, great and small, near and close, empty and full. Contrary to the Cartesian myth of a pure thinking faculty, our conceptual and animate intelligences are intimately linked.

By contrast, machine intelligence really is purely analytical. It has no scaffolding linking it to the vibrant sentience of life. Regardless of its level of sophistication and power, it is nothing other than a pattern recognition device. AI theoreticians tend to think of intelligence as substrate independent—meaning that the set of patterns and linkages comprising it could in principle be separated from its material base and exactly replicated elsewhere, such as when you migrate the data from your old computer to a new one. That is true for AI, but not for human intelligence.[7]

The dominant view of humanity as defined solely by conceptual intelligence has contributed greatly to the dualistic worldview underlying many of the great predicaments facing society today. The accelerating climate crisis and ecological havoc being wreaked on the natural world ultimately are caused, at the deepest level, by the dominant instrumentalist worldview that sees humans as essentially separate from the rest of nature, and nature as nothing other than a resource for human consumption.

Once, however, we recognize that humans possess both conceptual and animate intelligence, this can transform our sense of identity as a human being. The most highly prized human qualities, such as compassion, integrity, or wisdom, arise not from conceptual intelligence alone, but from a complex mélange of thoughts, feelings, intuitions, and felt sensations integrated into a coherent whole. By learning to consciously attune to the evolved signals of our animate consciousness, we can develop an integrated intelligence: one that incorporates both conceptual and animate fully into our own identity, values, and life choices.

Once we embrace our own animate intelligence, it’s natural to turn our attention outward and appreciate the animate intelligence emanating from all living beings. Acknowledging our shared domain of intelligence with the rest of life can lead to a potent sense of being intimately connected with the animate world. If conceptual intelligence is a cognitive peak of specialization that distinguishes us from other animals, it is our animate intelligence that extends throughout the rest of the terrain of existence, inviting a shared collaboration with all of life.

Other cultures have long possessed this understanding. Traditional Chinese philosophers saw no essential distinction between reason and emotion, and used a particular word, tiren, to refer to knowing something, not just intellectually, but throughout the entire body and mind. In the words of Neo-Confucian sage Wang Yangming, “The heart-mind is nothing without the body, and the body is nothing without the heart-mind.”[8] Indigenous cultures around the world share a recognition of their deep relatedness to all living beings, leading them to conceive of other creatures as part of an extended family.[9] For Western culture, however, which is now the globally dominant source of values, this orientation toward integrated intelligence is rare but acutely needed.

Aligning with integration

These distinctions, theoretical as they might appear, have crucially important implications as we consider the onset of advanced artificial intelligence and how to wrestle with the alignment problem. Upon closer inspection, the alignment problem turns out to be a conflation of two essentially different problems: The question of how to align AI with human flourishing presupposes an underlying question of what is required for human flourishing in the first place. Without a solid foundation laying out the conditions for human wellbeing, the AI alignment question is destined to go nowhere.

Fortunately, much work has already been accomplished on this topic, and it points to human flourishing arising from our identity as a deeply integrated organism incorporating both conceptual and animate consciousness. The seminal work of Chilean economist Manfred Max-Neef sets out a comprehensive taxonomy of fundamental human needs, incorporating ten core requirements such as subsistence, affection, freedom, security, and participation, among others. While these needs are universal, they may be satisfied in myriad ways depending on particular historical and cultural conditions. Furthermore, as Earth system scientists have convincingly demonstrated, human systems are intimately linked with larger biological and planetary life-support systems. Sustained human wellbeing requires a healthy, vibrant living Earth with intact ecosystems that can readily replenish their own abundance.[10]

What, we might ask, might an AI look like that was programmed to align with the principles that could enable all life, including human civilization, to flourish on a healthy Earth?

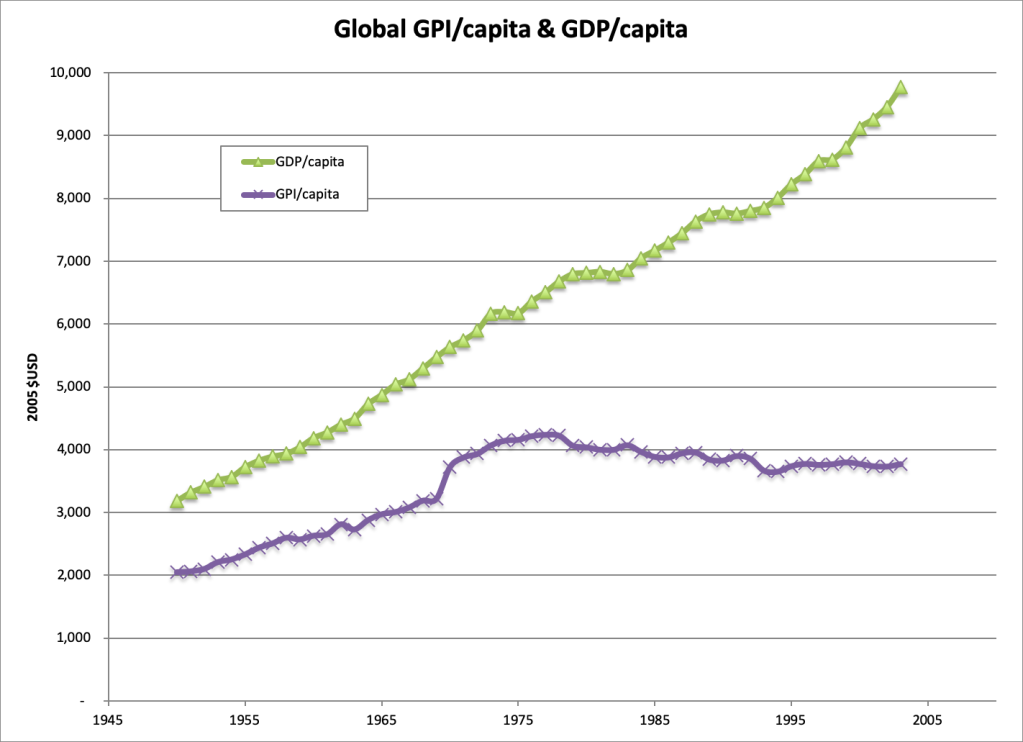

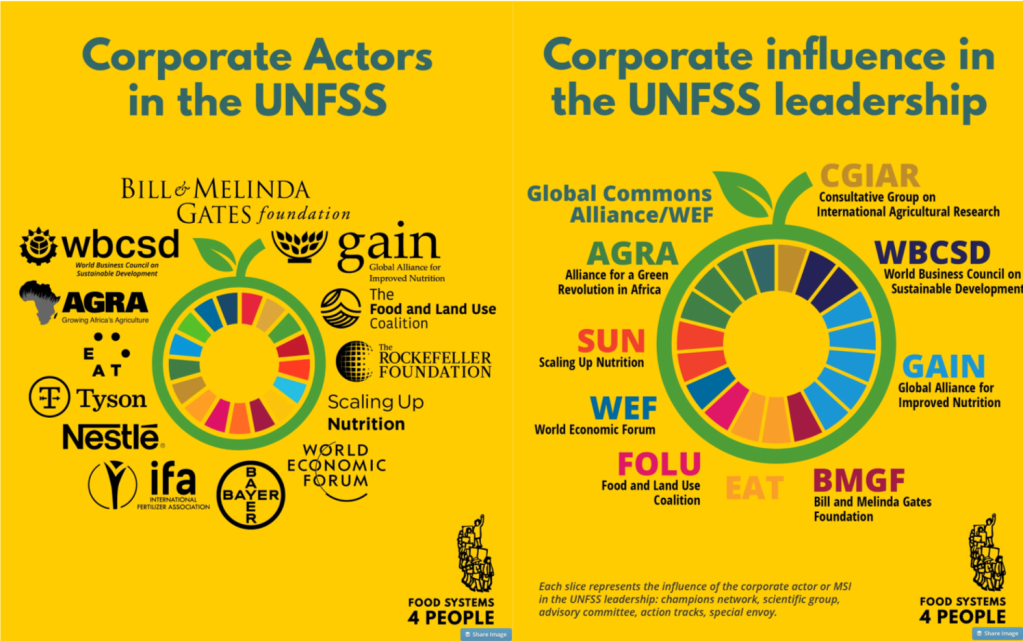

When we consider, however, how far the requirements for flourishing are from being met by the vast majority of humans across wide swaths of the world today, this brings to light that the alignment problem is not, in fact, limited to the domain of AI, but is rather a fundamental issue underlying the economic and financial system that runs our modern world. As I’ve discussed elsewhere, global capitalism, as manifested in the limited liability corporation, may itself be understood as an embryonic form of misaligned AI: one where the overriding goal of maximizing shareholder value has ridden roughshod over fundamental human needs, and has led to the current metacrisis emanating from a confluence of rising inequality, runaway technology, climate breakdown, and accelerating ecological devastation. In this respect, as pointed out by social philosopher Daniel Schmachtenberger, advanced AI can be viewed as an accelerant of the underlying causes of the metacrisis in every dimension.

Emerging from this dark prognostication, there is a silver lining affording some hope for a societal swerve toward a life-affirming future. When analysts consider the great dilemmas facing humanity today, they frequently describe them as “wicked problems”: tangles of highly complex interlinked challenges lacking well-defined solutions and emerging over time frames that don’t present as clear emergencies to our cognitive systems which evolved in the savannah to respond to more immediate risks. As an accelerant of the misalignment already present in our global system, might the onset of advanced AI, with its clear and present existential danger, serve to wake us up, as a collective human species, to the unfolding civilizational disaster that is already looming ahead? Might it jolt us as a planetary community to reorient toward the wisdom available in traditional cultures and existing within our own animate intelligence?

It has sometimes been said that what is necessary to unite humanity is a flagrant common threat, such as a hypothetical hostile alien species arriving on Earth threating us with extinction. Perhaps that moment is poised to arrive now—with an alien intelligence emerging from our own machinations. If there is real hope for a positive future, it will emerge from our understanding that as humans, we are both conceptual and animate beings, and are deeply connected with all of life on this precious planet—and that collectively we have the capability of developing a truly integrative civilization, one that sets the conditions for all life to flourish on a regenerated Earth.

Jeremy Lent is author of the award-winning books, The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity’s Search for Meaning, and The Web of Meaning: Integrating Science and Traditional Wisdom to Find Our Place in the Universe. He is the founder of the Deep Transformation Network.

[1] Vinge, V. (1993). “What is The Singularity?” VISION-21 Symposium(March 30, 1993); http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I._J._Good.

[2] For an in-depth discussion of this historical process, see my book The Web of Meaning: Integrating Science and Traditional Wisdom to Find Our Place in the Universe, Chapter 3.

[3] Carl Safina, Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 2015), pp. 92, 211, 236–7; Lucy A. Bates, Joyce H. Poole, and Richard W. Byrne, “Elephant Cognition,” Current Biology 18, no. 13 (2008): 544–46; Kieran C. R. Fox, Michael Muthukrishna, and Susanne Shultz, “The Social and Cultural Roots of Whale and Dolphin Brains,” Nature Ecology & Evolution 1, November (2017): 1699–705; Katharina Kropshofer, “Whales and Dolphins Lead ‘Human-Like Lives’ Thanks to Big Brains, Says Study,” The Guardian, 16 October, 2017.

[4] Paco Calvo, et al., “Plants Are Intelligent, Here’s How,” Annals of Botany 125 (2020): 11–28; Eric D. Brenner et al., “Plant Neurobiology: An Integrated View of Plant Signaling,” Trends in Plant Science 11, no. 8 (2006): 413–19; Anthony Trewavas, “What Is Plant Behaviour?”, Plant, Cell and Environment 32 (2009): 606–16; Stefano Mancuso, The Revolutionary Genius of Plants: A New Understanding of Plant Intelligence and Behavior (New York: Atria Books, 2018; Suzanne W. Simard, et al., “Net Transfer of Carbon between Ectomycorrhizal Tree Species in the Field,” Nature 388 (1997): 579–82; Yuan Yuan Song, et al., “Interplant Communication of Tomato Plants through Underground Common Mycorrhizal Networks,” PLoS Biology 5, no. 10 (2010): e13324.

[5] Boyce Rensberger, Life Itself: Exploring the Realm of the Living Cell (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), pp. 62–6; Brian J. Ford, “Revealing the Ingenuity of the Living Cell,” Biologist 53, no. 4 (2006): 221–24; Brian J. Ford, “On Intelligence in Cells: The Case for Whole Cell Biology,” Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 34, no. 4 (2009): 350-65; Evan Thompson, Mind in Life: Biology, Phenomenology, and the Sciences of Mind (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007), p. ix.

[6] Gerald M. Edelman, and Giulio Tononi, A Universe of Consciousness: How Matter Becomes Imagination (New York: Basic Books, 2000); Antonio Damasio, The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness (New York: Harcourt Inc., 1999); Daniel Kahneman, Thinking Fast and Slow (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2011).

[7] For a lucid explanation of why human intelligence is not substrate independent, see Antonio Damasio, The Strange Order of Things: Life, Feeling, and the Making of Cultures (New York: Pantheon 2018), pp. 199–208.

[8] Donald J. Munro, A Chinese Ethics for the New Century: The Ch’ien Mu Lectures in History and Culture, and Other Essays on Science and Confucian Ethics (Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 2005), p. 24; Yu, N. (2007). “Heart and Cognition in Ancient Chinese Philosophy.” Journal of Cognition and Culture, 7(1-2), 27-47. For an extensive discussion of the integrative nature of traditional Chinese thought, see my book The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity’s Search for Meaning (Amherst, NY: Prometheus, 2017), chapters 9 and 14.

[9] Four Arrows (Don Trent Jacobs), and Darcia Narvaez, Restoring the Kinship Worldview: Indigenous Voices Introduce 28 Precepts for Rebalancing Life on Planet Earth (Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books, 2022).

[10] Max-Neef, M.A., 1991. Human Scale Development: Conception, Application and Further Reflections. Zed Books, New York; Johan Rockström, et al., “A Safe Operating Space for Humanity,” Nature 461 (2009): 472–75; William J. Ripple, et al., “World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice,” BioScience 67, no. 12 (2017): 1026–28.