This week, here in Paris, we saw what may turn out to be a major milestone in the history of humankind. I’m not talking about COP21, but about a 2-day tribunal which, although having no legal standing or powers of enforcement, may turn out to have an even greater impact on the future direction of our world. It was a Rights of Nature tribunal, and it represents the most recent step in an important and hopeful journey for humanity – the recognition and expansion of intrinsic legal rights.

Some historical context helps. Back in 1792, Thomas Paine, author of The Rights of Man, was tried and convicted in absentia by the British for seditious libel. Paine’s troubles arose from the fact that he was blazing a new trail that has since become the bedrock of modern political thought: the inherent rights of human beings.

Paine’s writing deeply influenced the composers of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, one of the most influential documents of modern history. “We hold these truths to be self-evident,” it declared, “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

These truths, while self-evident to the founding fathers, were radical ideas for that time, so much so that even those who signed the Declaration applied them sketchily, not even considering that they might apply equally to the Africans forced to work as slaves in their plantations.

By the middle of the twentieth century, in response to the totalitarian horrors of genocide, the world came together to create a new stirring vision that would apply equally to all human beings: the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights. For the first time in history, fundamental human rights were universally recognized and given legal protection.

Of course, these rights continue to be abused in all kinds of ways. But new norms had been established, and nowadays, following the formation of the International Criminal Court, when a tyrant wreaks havoc on his population, he knows that he might have to face legal consequences from the rest of the world.

As we enter into the heart of the twenty-first century, a new set of crises face humanity: the ravages of climate change, deforestation, industrial agriculture, the destruction of natural habitats, and the impending Sixth Extinction of species. Like Paine and his associates, a new group of visionaries are expounding a revolutionary concept that responds to our troubled era: the Rights of Nature.

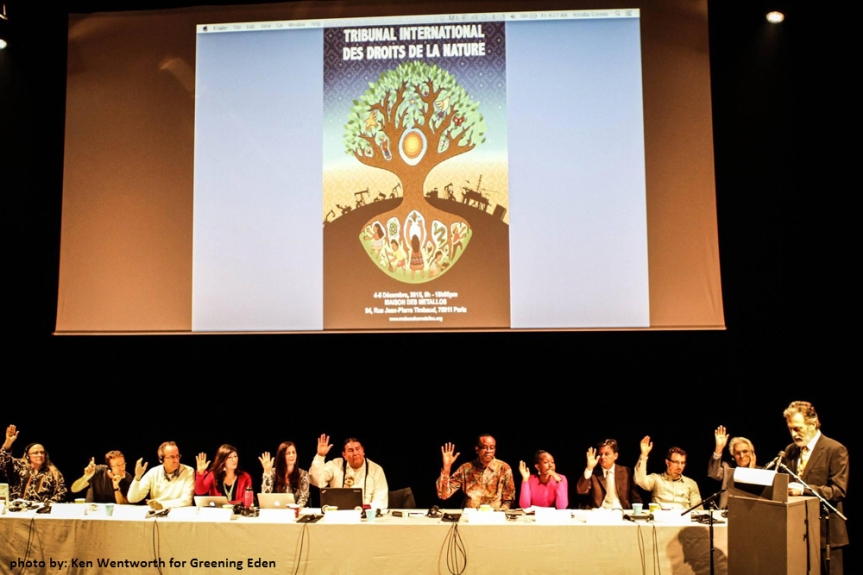

This week in Paris, this group held a 2-day Rights of Nature Tribunal, part of which I had the honor to attend and film. The Tribunal was based on the idea that nature also has rights, just like humans. Its foundational document is a Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth, calling for the “universal adoption and implementation of legal systems that recognize, respect and enforce the rights of nature.”

The Tribunal was a formal proceeding, with a panel of thirteen judges consisting of internationally renowned lawyers, academics and prominent activists. There were Prosecutors for the Earth, along with witnesses – comprising human victims of crimes against nature along with expert witnesses. They heard a wide variety of cases, ranging from the destruction of the Great Barrier Reef, the devastation of boreal forests by tar sands extraction in Alberta, Canada, and oil exploitation plundering sacred native lands in Yasuní, Ecuador. In each case, after hearing from prosecutors and witnesses, the Tribunal considered the evidence and passed judgement.

The same year that the UN promulgated its Universal Declaration of Human Rights, it also defined the crime of genocide for the first time, adopting a convention to outlaw it across the world. Similarly, the Rights of Nature Tribunal focused much attention on the crime of ecocide, defined in legal terms as “any act or failure to act which causes significant and durable damage to any part or system of the global commons, or threaten the safety of humankind.” Through the lens of the ecocide concept, the Tribunal assessed the “financialization” of Nature through market mechanisms as a crime rather than a solution, crimes committed by the Agro-Food Industry, and crimes being committed against those defending Mother Earth.

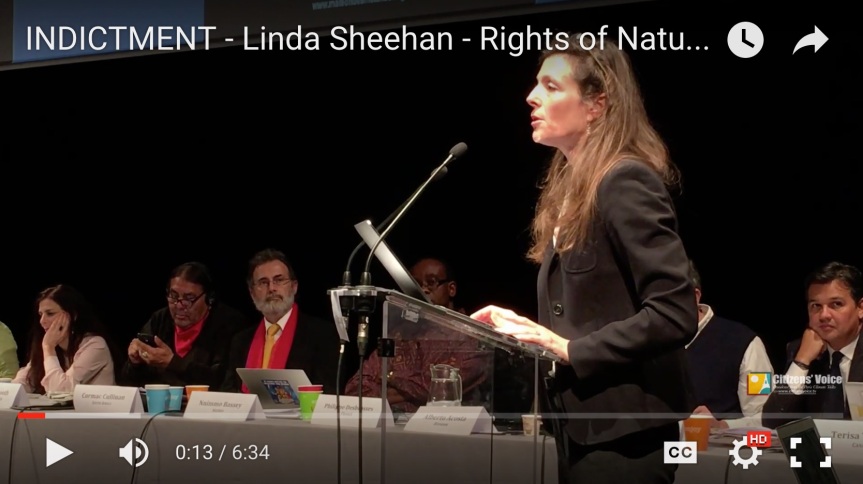

Meanwhile, crimes committed against nature have been happening not only in remote places – what journalist Chris Hedges has termed our civilization’s “sacrifice zones” – but only a few miles from the Tribunal in the Le Bourget district just outside Paris, where world leaders are negotiating plans to respond to climate change. Summing up the proceedings on the last day, environmental lawyer Linda Sheehan took the stand to indict the working draft of the COP21 agreement for failing to comply with the United Nations’ own laws, and for ignoring the rights of nature and the world’s indigenous peoples.

The significance of the Tribunal, as described by the founder of the Rights of Nature movement, Cormac Cullinan, in his summing up, is that it establishes a prototype for what is possible, a new legal discourse that could become mainstream before too long. The Tribunal, as he put it, is “setting the standard for new norms in the relationship between human civilization and the natural world.”

It took over a hundred and fifty years before the grand vision of Thomas Paine would be endorsed by the entire world through the UN’s declaration. We don’t have that long nowadays. But with the speed in which ideas travel in today’s world, we can be hopeful that these new norms will become a commonplace in our own lifetime. Each of us has a part to play in this, by opening our minds to these new possibilities, and turning them into realities on the ground, just like the citizens of Ecuador and Mendocino County.

By the end of this century, if our civilization continues to exist, it may be in no small part due to the ideas propounded today about the Rights of Nature. Perhaps, at that time, someone will look back and see this week’s Tribunal as a milestone in the global embrace of the “truths” that may, by then, seem “self-evident” to people everywhere.

Bravo Jeremy! This beautifully sums up the importance of a proceeding that has been hard for me to fully grasp. Thank you for being there and giving us your first person account.

LikeLike