Many people claim that evolution has a direction toward increased complexity—and that humans represent its apex. Our destiny, they declare, is to break out of our earthly limitations and explore the galaxy. Although an intoxicating vision for some, the rise of human civilization has been a double-edged story. Until humans learn to enhance life on Earth rather than destroy it, we’re not ready ethically to reach for the stars.

Excerpted from The Web of Meaning: Integrating Science and Traditional Wisdom to Find Our Place in the Universe (published earlier this month in the UK, and available July 13 in the US),

Complexity, cooperation, and civilization

Life’s glorious triumph on Earth has been achieved, not just through increased complexity, but also increased cooperation. In fact, the two go hand in hand. When individuals cooperate, it allows them to specialize in what they do best, thus promoting diversity and greater complexity. Whether it was single cells combining to create multicellular organisms, or insects collaborating to form colonies, the great phase transitions of life have all required massive upsurges in cooperation.

Many researchers have pointed out that building cooperation doesn’t come easily. A perennial problem for cooperating groups throughout the history of life—whether bacteria, organisms, or communities—is the risk of freeloaders: those that take advantage of the benefits of the group without making their fair contribution. If there are too many of them, they undermine the effectiveness of the group and may cause it to disintegrate. Genetic relatedness is one way evolution solved this problem: cells and organisms evolved to cooperate more closely with others that share their genes. But cooperation extends far beyond genetic affiliation.

Ultimately, the crucial success factor for cooperation at increasing levels of scale is integration—a state of unity with differentiation. In a fully integrated system, each part maintains its unique identity while operating in coordination with other parts of the system. To do so, the parts must remain in intimate feedback loops of communication with a large number of related parts. Each of the systems we’ve been looking at—cells, organisms, ecosystems, and Gaia—is a paragon of this type of integration. In fact, integration is a defining characteristic of any purposive, self-organized entity.

As life succeeded in integrating ever larger systems, it kept improving its negative entropy (or negentropy): the process of turning entropy into islands of self-organization that is a defining feature of all living systems. Larger animals utilize energy more efficiently than smaller ones, and larger colonies of insects are more effective at staving off entropy than smaller ones. The rise of human civilization itself may be portrayed as a series of enhancements in energy utilization. Agriculture, as anthropologist Leslie White has laid out, harnessed the negentropy of horses, cows, and sheep, who spent their days consuming the sun’s energy stored in plants, and then made it available to humans in the form of work, milk, wool, and meat. Further technological advances allowed humans to exploit the energy of the natural world ever more efficiently.

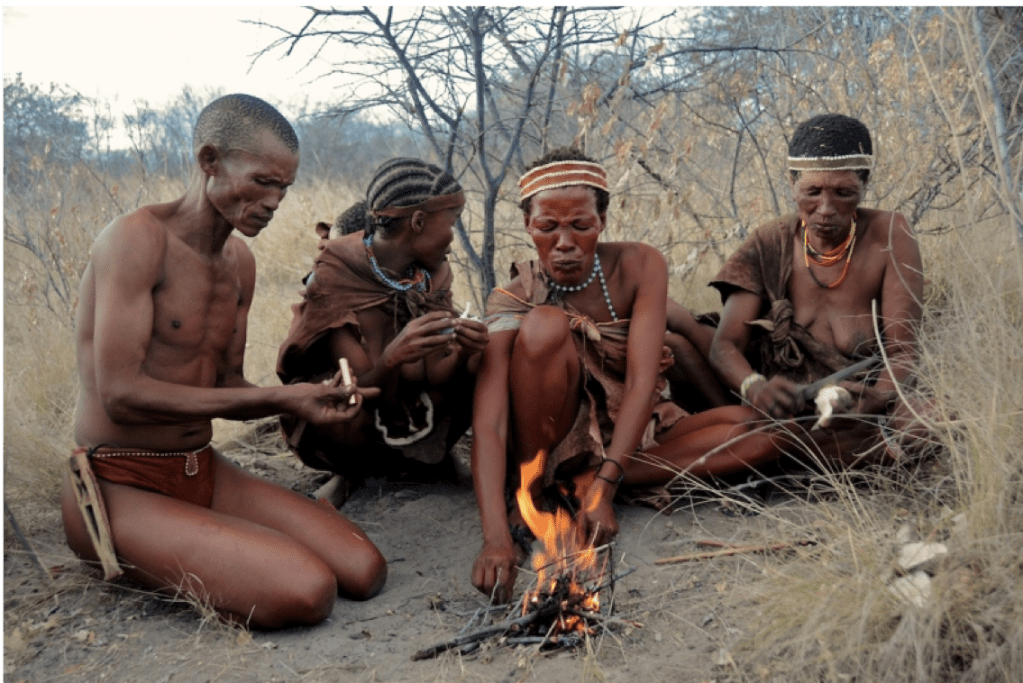

As with the other great phase transitions of life, underlying humanity’s achievements in agriculture and technology was an increase in cooperation. Humans are by far the most cooperative of primate species, and this—more than any other factor—is the key to our species’ success. As pre-humans evolved in bands of nomadic hunter-gatherers, they developed a sophisticated social intelligence, enabling them to collaborate closely with each other. Early hominids also faced the freeloader problem, and the characteristics they evolved to solve it became an intrinsic part of human nature: a powerful instinct for fairness, combined with a drive to punish those who flagrantly break the rules, even at one’s own expense. Many of the qualities we prize in a person, such as compassion, generosity, honesty, and altruism, are the results of our hunter-gatherer ancestors evolving the aptitude to collaborate successfully as a group.

Like earlier evolutionary transitions, enhanced cooperation in humans enabled greater specialization. Soon after the emergence of agriculture, cities appeared, replete with all kinds of specialists—artisans, healers, warriors, and priests—who, by plying their unique trades, together formed the backbone of civilizations around the world. Like insect colonies, cities become more efficient at negentropy the bigger they get. With each doubling of population size, a city only needs about 85% more infrastructure, such as roads, water pipes, gas stations, and grocery stores. In fact, a city can be understood as a form of superorganism, showing many of the self-organized characteristics that we’ve come to see in all living entities ranging from cells to ecosystems.

The scale of human connectivity, of course, extends far beyond individual cities. In the modern era, with instant global connectivity through the internet, humans have woven a worldwide web like nothing Earth has seen in its entire existence. Does humanity’s ascendancy represent the next step in life’s continued evolution toward ever greater complexity? Thoughtful observers of different stripes—scientists, philosophers, and visionaries—answer with a strong affirmative. Evolution, they claim, has a direction. From bacteria to eukaryotes to multi-celled organisms, from plants to reptiles and then to mammals, life, they argue, has a destiny that culminates inevitably in the emergence of creatures like us—possessing complex brains with the ability to become self-aware and perhaps ultimately direct our own future evolution toward even greater complexity.

It’s an intoxicating vision for some. However, if we look more closely into this narrative, we find it contains elements that are not quite as triumphant as we might wish. It’s a doubled-edged story—and those edges form the parameters of much that we’ll explore later in this book.

Eligible for the Federation?

The idea of inevitable progress as a cosmic law traces its pedigree back to seventeenth-century Europe, but it was a twentieth-century visionary, theologian-cum-paleontologist Teilhard de Chardin, who gave it a scientific tincture, tying it in to modern evolutionary theory. Pointing to the increasing complexity of life, Teilhard triumphantly placed humanity at its apex. “Life physically culminates in Man,” he wrote, “just as energy physically culminates in life.” Teilhard saw this inevitable progression continuing toward what he called the Omega Point—the ultimate stage of evolution in which all distinctions between artificial and natural are dissolved, when humanity’s consciousness will fuse with the entire natural world to form one unified organism of embodied intelligence.

More recently, leading techno-visionaries have taken up Teilhard’s vision but jettisoned nonhuman nature from the grand narrative. In his bestseller, The Singularity Is Near, Google executive Raymond Kurzweil prophecies a future where humanity’s conceptual intelligence fuses with machines, leaving animate existence in the dust. “There will be no distinction, post-Singularity,” he declares, “between human and machine or between physical and virtual reality.” Similarly, prominent physicist Max Tegmark views the inevitable appearance of super-intelligent AI as Life 3.0—overcoming the physical constraints of human beings (“Life 2.0”) and the rest of nature (“Life 1.0”). Frequently, these visions foresee a future intelligence leaving Earth behind, expanding through the Milky Way and then into other galaxies, spreading the higher consciousness and advanced intelligence required for converting the entire universe into a font of negative entropy, perhaps even one day, in the far distant future, repealing the Second Law of Thermodynamics itself.

There is something wildly inspirational in this kind of vision, yet it contains a foundational flaw that must be identified and fixed before it could ever take off. Since these visions extend into the realm of imagined futures, it seems fitting to approach them from the perspective of one of science fiction’s best-loved sagas—the Star Trek series. As Star Trek fans (I’m one of them) can attest, the future it envisages, with all its challenges and existential threats, is largely benevolent on account of the values of the United Federation of Planets. The Federation only allows other planetary civilizations to join if, after a thorough evaluation, they meet its ethical criteria, which include an affirmation of “the fundamental rights of sentient beings,” and faith “in the dignity and worth of all lifeforms.”

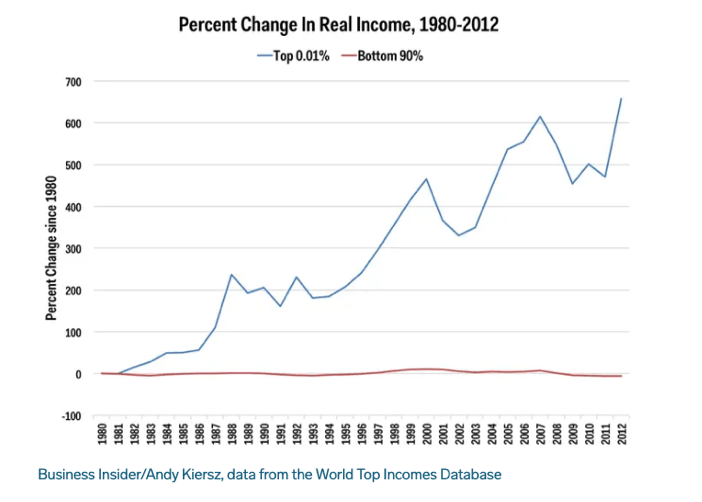

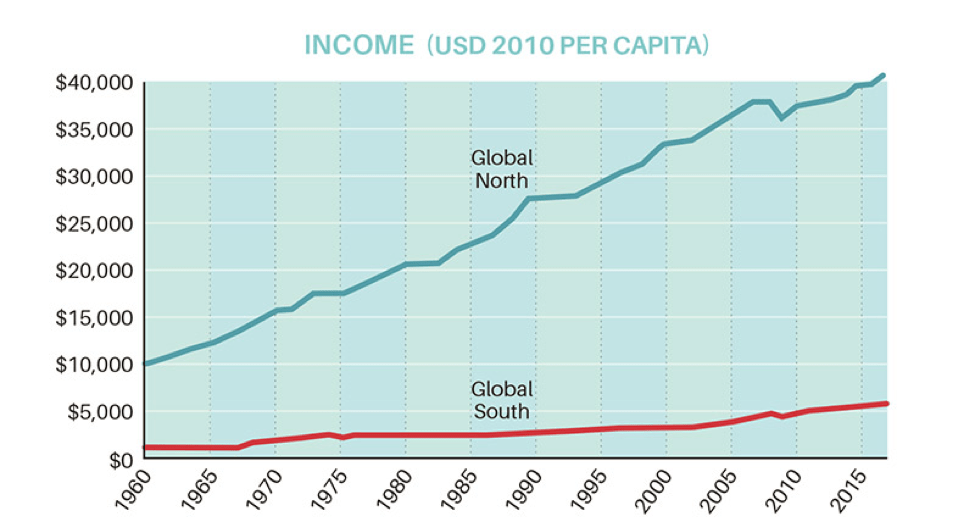

Would our current civilization be eligible to join the Federation if they evaluated us today? The only realistic answer is an emphatic “No.” Quite apart from the extreme inequities among our own species, forcing billions to live without basic rights such as a home, education, or food security, humanity has been systematically destroying the welfare of other sentient beings on Earth without any regard to their dignity or worth. The rollcall of humanity’s depredations against nature is vast. Some of our most egregious transgressions would have to include the willful torture of billions of domesticated animals in factory farms; the vast demolition of wildlife habitat; the pollution of Earth’s waterways and oceans; the indiscriminate use of deep sea trawlers that decimate fish populations; and the massive conversion of vibrant ecosystems into huge monocrop plantations. The list goes on and on. As a result of the boundless havoc caused by our global civilization, Earth is now experiencing the sixth mass extinction of species since life began on our planet. The sorrowful reality is that, if humanity did succeed in developing the technologies to explore the universe, without first changing its ethical moorings, then a dismal fate would await other less powerful sentient beings out there. If Federation officials were to consider us for entry at this stage in human history, we wouldn’t stand a chance.

Far from being the next step in life’s evolution, humanity’s ascendancy in its current form represents a major step in the wrong direction. We can comprehend this better when we consider the importance of integration as the key to life’s success in continually improving negentropy. In a truly integrated system—consistent with Federation ethics—each entity possesses intrinsic dignity and worth, pursuing its own purpose as part of the larger whole. Our civilization, however, has built its relationship with the rest of nature, not on integration, but on dis-integration. It is based on dominating the natural world with no consideration for its wellbeing. Through our irresponsible use of fossil fuels, we have created imbalances in Gaia’s own health that are causing pernicious damage to countless species as well as our own. Through our conversion of ecosystems into monocrops, poisoning of waterways, annihilation of coral reefs, and emptying the oceans of fish, we are quite possibly the greatest force for entropy that Gaia has experienced in billions of years. Rather than integrating with the rest of life, as Teilhard may have envisaged, we are ruthlessly destroying life, eradicating its precious complexity—and are doing so at an ever-accelerating pace.

There are some who, appalled by our species’ impact on the living Earth, consider humanity to be like a malignant cancer consuming Gaia. While this may be a fair depiction of our current civilization, it certainly need not hold true for humanity as a species. The rise of conceptual intelligence in humans has given us exceptional powers that can be used both beneficially and destructively. However, just as we’ve seen how each of us can develop an integrative intelligence that combines our embodied experiences, humans collectively have the potential to develop a far more integrated relationship with the rest of nature. Technology doesn’t have to be used to destroy the complexity of living systems—if established on a different ethical basis, it could be developed to work in harmony with natural processes, promoting Gaia’s overall negentropy.

Through the rest of this book, we’ll explore what it means to live in a way that enhances life’s deep purpose rather than working against it. We’ll discover how, as a civilization, we have the potential to follow a path of integration that could lead to symbiotic flourishing for humanity and Gaia together—a path that just might lead, one day in the distant future, to being welcomed into the United Federation of Planets with open arms.

Explore The Web of Meaning further on Jeremy Lent’s website. The book is available for purchase now in the UK and preorder in the USA/Canada.